In December of 1979, I was part-way through eighth grade at the Seventh-Day Adventist Pacific Union College Elementary school in Angwin, CA, 94508.

My father taught in the college’s Religion department but he was being shipped with my mother to Washington D.C. to prepare a defense of his heretical views. (Read the Wikipedia entry.)

I thought I was condemned to move too and I didn’t like that. I felt that every time I started to get halfway close to people, we had to move. I moved all around in my first four years while my mother Gwen was dying of bone cancer and I had various care-givers.

Then my father remarried and we all moved to England for 18 months so dad could do a Ph.D. at Manchester University. We returned to Avondale College in Australia in 1972. I was six.

My dad followed Ellen G. White‘s teachings about holding kids out of school for as long as possible. I finally started my formal education in second grade at age eight. I think this late start severely cost me in developing social skills.

In May 1977, when I was eleven, we moved to the Seventh-Day Adventist Pacific Union College in the Napa Valley. I liked it there and I didn’t want to leave.

I think it was in December of 1979 that my classmate Andy Muth invited me to his home for Sabbath lunch. It was the first time a classmate had invited me over on the Sabbath. Andy didn’t want to. His mother made him. He was scared of my big mouth. I was a verbally aggressive kid. I enjoyed cutting people down.

I was very excited by the invite. It sucks when you’re not popular and you have to spend most of your life on your own.

Andy’s home had a whole different emotional temperature than mine. You have to understand that my father is a great man. He has two PhDs and he’s a gifted evangelist. He can mesmerize a crowd. Thousands of people believe that he’s changed their life.

So dad’s a double-threat. He can write academic books and he can speak to the common man about the great issues of life.

Dad didn’t just live his principles on the pulpit. He embodied them each day. I never saw him lose his temper and act out of control. He’s very controlled. Dedicated. He feels a mission to show people Christ crucified.

Dad didn’t mess around with his life. He didn’t waste it playing games or pursuing hobbies. He was a good father. He’d play Monopoly with me when I was a kid and kick a ball around for exercise.

My home was often cold. Literally. Dad believed in the virtues of fresh air, even in winter. He’d wrap up in blankets and leave the windows open and encouraged us to follow his example. If I’d shut the windows, he’d later come around and open them. In such a battle, the one who opens windows always wins. It’s easier to let warm air out than to keep it in.

Today I love a warm home. I keep things in my apartment a few degrees warmer than most people like. It’s my over-reaction to my childhood.

I hated being cold. I constantly dreamed I’d be adopted by a warm family, yet, whenever I thought through the specifics, I always concluded that the benefits of my own home outweighed the disadvantages. I loved having a dad who was a big shot and who was accomplishing great things in the world and knew great people and knew how to unlock books and explain important matters to thousands of people.

My father lived by the dicta that great people discuss ideas, not people. Our table talk was about philosophy, history and my father’s theological battles. Ordinary matters, such as girls, were forbidden (not explicitly, just by my father’s stern example, which my stepmother generally fell in with).

My parents did their best by me. They gave me far more than they had growing up. They loved me and they disciplined me and they gave me guidance about how to lead a good life. They connected me with God and with a religious community. I have no complaints. The things they forbade in the home and that I later came to enjoy, well, my enjoyment was all the sweeter for having once been denied.

So there I was in the Muth home after church that Sabbath afternoon. It was my first time there even though I’d known the family since I arrived in America the summer of 1977.

The first thing that struck me was the absence of tension. The two parents and their two kids were constantly kidding each other. These were fundamentally happy people. They weren’t constantly striving to be great. They weren’t weighed down by intellectual disputes. They didn’t regard the outside world as an enemy.

I loved the temperature in the Muth home. It was warm. It was emotionally warm. It was physically warm. It was a warm happy place.

It was probably a cold winter’s day outside but inside was warm and welcoming.

My dad was dedicated to the health message of the Seventh-Day Adventist church. For my own good, I wasn’t allowed to drink with my meals. No water. No juice. And certainly no soda.

Due to its high fat content, peanut butter was severely limited. Just a thin spread was all I was allowed.

On this day, however, that all changed. I could drink all the juice I wanted. I could eat all the peanut butter I wanted. I could eat and drink anything I wanted.

Religion does’t have to deform a family. It doesn’t have to end all pleasure in life. It doesn’t have to cut you off from those around you. It can be an aid to a good life.

You probably don’t understand my upbringing. Religion was a terribly swift sword. My parents basically lost contact with their families when they converted to Seventh-Day Adventism in their teens and took on this weird life.

I grew up not knowing what a niece or a nephew were. I didn’t know what constituted a cousin. I was really shaky about uncle and aunt. I had almost no contact with my relatives and those few times I did, it was very awkward. They were secular and my family was religious and we seemed to have nothing in common.

I didn’t understand home and family as happy places. I was more familiar with them as battle stations. They were instruments for regrouping before renewing one’s righteous assault on the wickedness of the world.

The Muth family, however, was completely different. They made me feel happy, a most unfamiliar feeling.

Until I met the Muth family, I felt like I was on the outside of life looking in. I was lost in fantasies of grandeur. I was terribly lonely and unhappy.

Once I was in with the Muths, I got to live life from the inside. I knew that no matter what happened, there would always be a place for me.

Living life from the inside means you’re connected to other people and that what you do matters. You affect people. You matter. You have a role in the play and a place at the table.

Mrs. Muth said she wanted me to be able to finish eighth grade with my class and that if I needed to, I could stay with their family.

I’ve been the recipient of much kindness in my life but I don’t think anything ever touched me as deeply as this. I was dreading the move to D.C. I didn’t want to leave my classmates before graduation. More than that, I wanted to be part of a normal loving family.

I didn’t get to stay with the Muths through June of 1980 when there was no escaping a trip back east. My family had arranged for me to stay somewhere else. Still, I got to be friends with Andy and spend a lot of time at his home over the next five years.

These were the happiest times of my life. Though my family moved 2.5 hours drive away in the fall of 1980 to Auburn, I kept coming back to PUC whenever I could to stay with the Muths.

I was a completely different person away from my parents. In my dad’s shadow, I was a skeleton of a human being. He was the lead actor and I was just an extra. Away from my parents, I was the lead in my own movie.

I always felt giddy when I was on my way to PUC and I always felt sad when I left. In my teenage perspective, one place was warm and full of community. The other place was remote and lonely. In one place I belonged and in the other place I was just serving time. One place was happy and one place was sad. One home was tense and one home rang laughter. One home constantly had people over and one home didn’t.

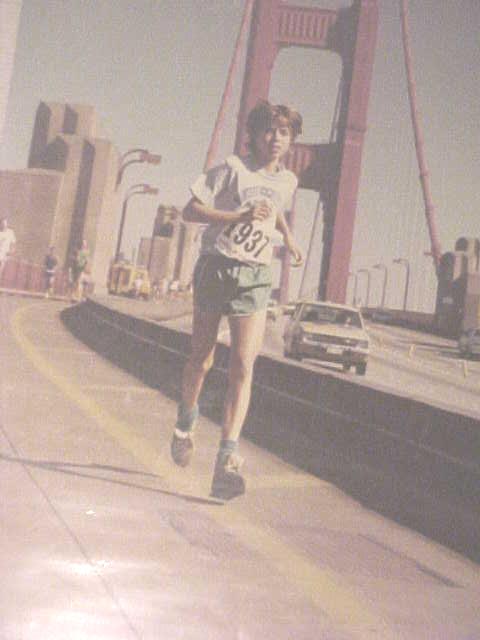

Running across the Golden Gate bridge in 1978 on my way to completing the San Francisco marathon in four-and-a-half hours.

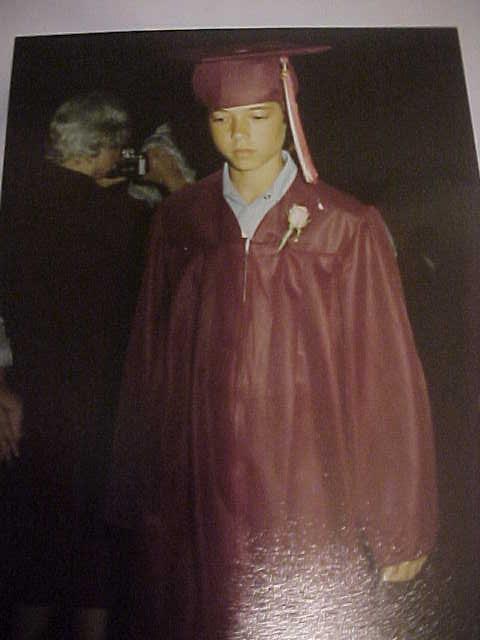

June 1980. My eighth grade graduation. I remember hugging some of my classmates afterwards and saying, “Can you believe we made it?”

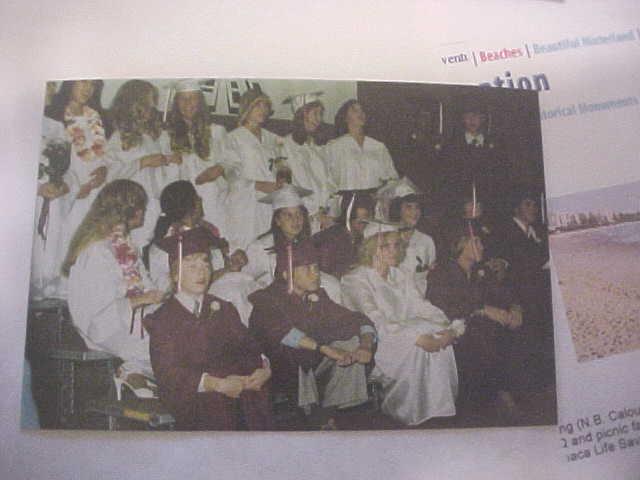

The night of my eighth grade graduation. I sit in the front row, wearing green socks, and staring off the left. The blonde on my left, Jeanie Clark, was the only girl whoever called me at my parent’s home. She was my almost girlfriend. We wrestled in the PUC pool during the summers of 1978 and 1979. The looker brunette behind me, Denise Bernard, was the object of my romantic desire from about 1977-1984. I haven’t seen her since June of 1984.

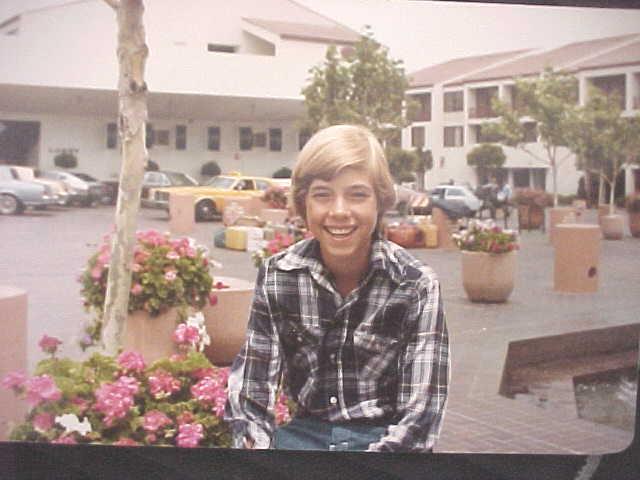

Outside one of my father’s meetings in Monterey in the summer of 1981.