“Problematic” is a favorite word among academics but they feel insulted and retreat into silence when you ask them to describe their hero system that renders so much of reality “problematic.” According to the Merriam_Webster dictionary, the third meaning of “problematic” is “having or showing attitudes (such as racial prejudice) or ideas (such as falsehoods) that are offensive, disturbing, or harmful.”

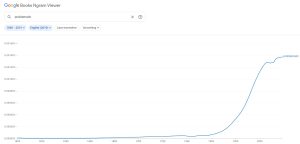

The Google NGram viewer shows that books didn’t use “problematic” much until the 1960s.

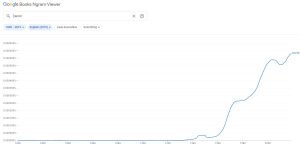

Similarly, the Google NGram viewer shows that books didn’t use “racist” much until the 1960s.

Racism is a made up moral category that had no currency until the 1960s. Somehow all the great moral thinkers throughout history prior to the 20th Century had no concern about this great evil.

If academics had the strength of their convictions and weren’t afraid of owning up to having a subjective partisan hero system just like everyone else, they’d just say “bad.” But talking about good and bad sounds Christian, so academics pretend to have transcended partisan hero systems, which is impossible.

When academics won’t admit distress because their subjective hero system has been violated, what do they do? As human beings, they must lash out at an offense, but they won’t fight back in a way that is true, raw and vulnerable (a la how American conservatives do when somebody desecrates their nation’s flag), so instead they subjugate their impulses to reference good and evil, and instead employ the careful language of the courtier cocooned in his buffered identity.

In his great 2014 book Rethinking Jewish Philosophy: Beyond Particularism and Universalism, Aaron W. Hughes wrote:

* Rosenzweig’s goal is extremely problematic because it is based on a series of essentialisms that emerge from a particularist rhetoric…

* …the juxtaposition of “Judaism” and “philosophy” is highly problematic, used as it is to serve potentially ideological or political ends.

* …Rosenzweig’s woefully inaccurate understanding and representation of Islam is based on his need to have a foil for his equally problematic and racially charged reading of Judaism.

* Rosenzweig’s essentialist characterization of Judaism and the Jewish people inscribes both with a set of highly problematic traits grounded in racial and nationalistic

politics.* …Maimonides and Rosenzweig—now seen as symbols for medieval and modern Jewish philosophy, respectively— succeed in creating authoritarian Judaisms based on a self-constructed rhetoric of authenticity and what amounts to a rather problematic reification of Jewish peoplehood.

* I suggest that such responses are not “authentic” precisely because authenticity is such a problematic term, one that is always just out of reach and is always constructed. Yet, problematically, Jewish philosophy—throughout its long and winding history—has been and continues to be invested in manufacturing such an authentically Jewish response.

If Professor Hughes sees the problems cited above, why doesn’t he just state the exact nature of the problem instead of resorting to euphemism? I emailed him about his love of the word “problematic”, but I didn’t get a response.

Why is the word “problematic” so commonly used by those on the political left?

It’s a strange word that I don’t really understand. It’s it’s always felt like a bit of a weasel word to me. I feel like there is always a more assertive and clear way to rephrase the statement.

I’ve spent about half my life in rural America and the other half in NYC and have many friends and family in both places. But I’ve never heard someone from the right describe something as “problematic”. I feel like it’s a word that has only come into use in the past decade or so and I’ve always cringed when I hear it used.

When I hear someone call a persons behavior “problematic”, it feels passive aggressive and vague. It’s like something a risk averse middle manager in a giant corporation would say.

* Because it’s more nuanced than good or bad. Let’s say someone says something mildly insensitive to you about a race, gender, or ability. You don’t want to ignore the comment. You could say “that’s bigoted” but that has a way of turning it onto a confrontation and makes the other person feels stupid and therefore disengage. Explaining that it’s problematic though let’s them know you don’t like why they said without judging them as a person and opens up for more dialog or clarification.

* The whole point of that word that it focuses on a behavior without framing the entire thing/person as a problem. It’s particularly applicable when describing things for which sensibilities have changed. For example, I was talking to a friend about Looney Toones cartoons from the 60s the other day. I was raised on those and I think they’re funny. But there is some insensitive shit in those old cartoons that was cool then, but not cool now. You could say, “those old cartoons are racist”, or you could say, “elements of them are problematic.”

* It’s used by people who understand that these humans and their behavior are complex and people and things aren’t one thing. It facilitates the conversation to have it in a way that is more nuanced.

* “Problematic” is rooted in social criticism and that project is popular with the academic left.

Language is a social construct and it partly signals our influences and social cues. By using language popular with a group, you signal an affinity and in-group association.

Its a gentler word and more indirect way of saying something is a problem, or bad, or wrong.

Gentler and indirect language can be a signal for either empathy or low self-confidence.

Women tend to have more empathy and less self-confidence on average compared to men.

Women also tend, on average, to be politically more left leaning than men.

Political affiliations have cultural and social group associations.

Putting it all together, “problematic” was popularized as a choice word for left wing social criticism because it appeals to sensibilities of critics and their audiences, and signals cultural group membership.

* It literally means that the subject of the sentence causes problems. And those problems may be complicated. I think its a great word to describe complex issues. Problems often have many facets to them.

* The notion of something being ‘problematic’ in discourse probably goes back to post-structuralism (“post-modernist”philosophers such as Foucault, Spivak, Said, etc.).

In the wake of such analysts—who showed how our structures of power influence what we consider to be knowledge (or truth)—we grew more conscious of how our language reinforces arbitrary, contingent (and usually unjust) power dynamics in society.

So, a movement derided as ‘political correctness’ seeks to undo or reorient the power dynamics by changing the language used in discourse. Problematic labels such as ‘The handicapped’ or ‘disabled’ become ‘people with disabilities’ or ‘the differently abled’ because defining a group of people by the abstract label society ascribes to it reinforces the implicit ‘othering’ (and ‘degrading’) of such labels.

If a person, like Kevin Spacey or ‘Cara Dune’ or Roman Polanski, are described as ‘problematic,’ it is because supporting those people would also reinforce implicitly a condoning (or elevating) of what they ‘stand for’ in the discourse. Platforming a problematic person does the same, according to this analysis.

However, as the author Yascha Mounck argued in his recent book those same post-structuralists were ambivalent about such strategies politically, since controlling the discourse is just what Power does, so PC prescriptions are exercises in using ‘knowledge as power,’ and this might lead to the backlash against the ‘authoritarian’ prescription of norms and behavior, seen in ‘cancel culture,’ ‘deplatforming’ endeavors, and self-censoring and protest culture on college campuses.

* Four syllables. May be tricky to spell. Good and Bad are so much easier.

Haley Swenson writes for Slate Mar. 24, 2016:

…the word problematic functions not as an opening into these deeper questions, but as a buzzy shortcut. It can allow the speaker to leave out the most critical arguments the audience needs to hear.

Various riffs on “that’s problematic” abound in edited, formal publications. A couple months ago, NPR deemed the colonial imagery in Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” music video “beyond problematic.” Slate has used the word at least a half-dozen times, and more than once in a headline. At the satirical Tumblr “Everything Is a Problem,” the author promises to “dispense problematics” on any subject or text readers send her way, offering a few lines of righteous indignation before rating different texts on a “problem” scale from one to five. A post about the puritanical, infighting tendencies of the left had the title “Entire Human Race Problematic—Left Can’t Work With Them.” Glancing through #problematic on Twitter suggests these satirists aren’t so far off. Sample tweets include “forgot how #problematic Ace Ventura is” and “Being #WOKE when 99.9% of the planet is a #PROBLEMATIC mess is exhausting. Honestly.”

Though some seem to take issue with the word’s implied political correctness or hypercritical attitude (see also: “-splaining” and the gender-neutral, singular “they”), the real weakness of problematic is that it is misleading and vague. Problematic—“constituting or presenting a problem or difficulty; difficult to resolve; doubtful, uncertain, questionable”—doesn’t actually capture the speaker’s complaint, which is about harm, not difficulty or uncertainty. The speaker is trying to suggest that something in the text constitutes a moral wrong. But problematic undercuts that critique by reframing the issue as a riddle to be unraveled.

The Oxford English Dictionary points to a problematic, as “A thing that constitutes a problem or an area of difficulty, esp. in a particular field of study.” This kind of problematizing is at the heart of academic inquiry—a collective recognition of the best theories and concepts the field currently offers, and then through research or argument or both, working within and around that best-established knowledge to account for things the field currently cannot. But when people don’t come to a discussion with the same understanding of the best theories of the field, or in the case of pop culture, a shared sense of what makes something offensive and what makes it morally and politically sound, calling something problematic seems to miss the point of argument. Instead of convincing someone a particular idea is a bad one, the arguments that follow “that’s problematic” tend to merely point out that the text contains an idea thought to be bad.

In the classroom, some of my most passionate students lean on the phrase when they take issue with a course reading or something insensitive a classmate said. The initially amorphous critique becomes a great place for me to open up discussion, to push the student to articulate his or her problem with something for a diverse crowd of thinkers. “What exactly did you think was wrong with what was said?” I might ask.

But in written work and in the social-media world of quick tweets and posts, “that’s problematic,” is far more unilateral, and far more of a rhetorical device than a dialogue starter. The phrase creates distance between the critic and the argument, placing the problem—racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.—in the text itself, rather than accounting for the subjective reasons the critic can see the harm the text is doing. Calling a text problematic erases the ways in which it interacts with readers’ own politics and experiences to produce its “problem.” We don’t get the full picture of harm done when a person of color watches a show about white people appropriating black culture, for instance. Social and cultural critique are only strengthened when the audience understands how the critic came to see something they missed.

Teresa M. Bejan wrote for The Atlantic Oct. 2, 2021:

Academics like me love to describe things as “problematic.” But what do we mean? We’re not saying that the thing in question is unsolvable or even difficult. We’re saying—or implying—that it is objectionable in some way, that it rests uneasily with our prior moral or political commitments.

For instance, when I described applying Ancient Greek free-speech ideals to social media as “problematic” in a recent article, I wasn’t saying that Socrates’s audience was impossible to please. I was saying that these practices were premised on exclusion in a way that modern egalitarians won’t like. Or when my Oxford colleague Amia Srinivasan describes stand-up comedy in Los Angeles as “problematic,” she’s not saying that she struggled to understand the jokes. She’s saying that they relied on sexism in a way that she—and everyone—should find morally bad.

In principle, every usage of the term problematic should be followed by an explanation. Is the situation or person in question unjust, immoral, or unfair? Racist, sexist, or otherwise bigoted? Wrongheaded, perhaps, or just plain wrong? All too often, the explanation never comes.

Rony Guldmann writes in his work in progress Conservative Claims of Cultural Oppression:

This is why the ethos of disengaged self-control and self-reflexivity would have been inconceivable for pre-moderns. The latter were not “buffered,” and this is why they could not have “stepped back” from their total teleological immersion into naturalistic lucidity. The anthropocentricity of pre-moderns was in the first instance a function, not of limited knowledge, but of their particular form of agency—the nature of the boundary, or lack thereof, between self and world. The crucial difference between moderns and pre-moderns is not that the former, unlike the latter, believe that their mental states originate in a physiological substratum interacting with the rest of the physical world (producing either “delight” or “annoyance” as Hobbes says), but that the former, unlike the latter, have a form of consciousness and identity within which this proposition is intelligible in the first place. A pre-modern couldn’t seriously contemplate the thought that “it just feels this way,” not because he was ignorant of his feelings’ causal springs, but because he was porous rather than buffered, because his basic, pre-theoretical experience of the world did not permit any clear-cut distinctions between the inner and the outer, between how things feel and how they are. This is a difference, not of beliefs, but of the pre-deliberative disposition to “distance” from one’s pre-reflective, pre-theorized layer of experience…