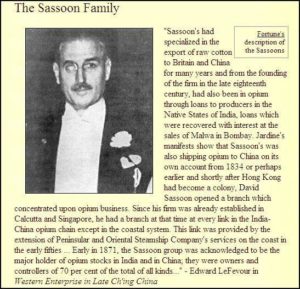

According to the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia entry on David Sassoon: “his business, which included a monopoly of the opium-trade, extended as far as Yokohama, Nagasaki, and other cities in Japan. Sassoon attributed his great success to the employment of his sons as his agents and to his strict observance of the law of tithe.”

Fortune magazine 1930s

When the Treaty of Nanking opened up China to British traders, Sassoon developed his textile operations into a profitable triangular trade: Indian yarn and opium were carried to China, where he bought goods which were sold in Britain, from where he obtained Lancashire cotton products. He sent his son Elias David Sassoon to Canton, where he was the first Jewish trader (with 24 Parsi rivals). In 1845 David Sassoon & Sons opened an office in what would soon become Shanghai’s British concession, and it became the firm’s second hub of operations.

In 1844, he set up a branch in Hong Kong, and a year later, he set up his Shanghai branch on the Bund to cash in on the opium trade.

“In Jewish history books, David Sassoon, an observant Jew, is remembered mostly for his philanthropy.”

On November 7, 1864, businessman David Sassoon, founding father of the Sassoon business dynasty, died in Pune, India. The trading empire he created spanned the globe, from what is now Mumbai on the western coast of India, via Shanghai and Hong Kong in China, all the way to London, England. It dominated world commerce in a number of commodities – most significantly opium – over the second half of the 19th century.

Sassoon was born in Baghdad in 1832 to Saleh Sassoon, a businessman and leader of that city’s Jewish community (the clan claimed descent from a Spanish family, the Ibn Shoshans). When David Sassoon, who like his father served as treasurer to the governors of Baghdad, clashed with one of them, Daud Pasha, he moved his family to Persia in 1826, and then to Bombay by 1832.

Sassoon initially owned a counting house and a carpet warehouse, but soon began trading in everything he could, including, most profitably, opium. When China’s emperor tried to outlaw the drug, which cut a wide swathe of destruction through the population of the country’s coastal regions, the British responded with war. The result was the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, which earned the United Kingdom a free hand in selling opium in China.

Sassoon established a triangle of trade, bringing Indian opium and cotton to China, where he received silver, tea and silk in exchange. He then carried these products to England for sale. Finished products from Britain, as well as cash, were then brought back to India where they were used to buy more opium. By the 1870s, David Sassoon had come to dominate the trade of opium to China, having pushed the British firm Jardine Matheson and the “Parsi” traders of Bombay out of the business.Sassoon’s eights sons all went into one branch or another of the family’s business empire, with the Sassoon presence being felt in Hong Kong, Shanghai (where they became major players in the realm of real estate), and India (where they had their own textile mills), among many other lands. The vast Sassoon Docks of Bombay, built by Sassoon’s son Albert Abdullah, were the first wet docks in the west of India.

In Jewish history books, David Sassoon, an observant Jew, is remembered mostly for his philanthropy, which included the construction of “Baghdadi” synagogues in Bombay (Magen David) and Pune (Ohel David), and also numerous schools and hospitals throughout India and other parts of Asia. David became a naturalized British citizen in 1853, although he continued to live in Pune.

His son Albert Abdullah moved to England, where he married into the Rothschild family and was elected to Parliament on the Conservative party’s ticket. Another son, Sassoon David Sassoon, was the father of Rachel Sassoon Beer, who became owner and editor of the Sunday Times at the turn of the century, and grandfather of the great poet of World War I, Siegfried Sassoon.

According to the 1944 Jewish Encyclopedia: “He employed only Jews in his business, and wherever he sent them, he built synagogues and schools for them. He imported whole families of fellow Jews…and put them to work.”

According to the 2003 book, Jews, Opium and the Kimono:

As British rule consolidated in India, there arose a greater need for employees to oversee their affairs. This need was a godsend for Bombay’s Babylonian Jews, who saw enormous financial potential in the opium trade. Transactions were discussed after prayers at the synagogues…

…it was his [David Sassoon’s] agents who set the prices for the various types of opium products…

The location of Shanghai, along the Whangpoo River, together with David Sassoon’s Jewish genius and foresight — were what made possible the passage of steamships into the Chinese hinterland, carrying valuable cargoes of opium…Wealthy Jews, such as Silas Hardoon, who had made his money in the opium trade and subsequently moved into real estate and respectability, built fabulous mansions in the most prestigious parts of the city [Shanghai]…

Opium, that staple drug of the Chinese people, infuriated the Chinese intelligentsia, who waged a stubborn battle against its use… [The Society to Combat the Opium Trade’s]…demands faced the open hostility of British government officials in India who regarded the destruction of the opium fields as a hard blow to the country’s economy. These officials were joined by the opium traders of Calcutta and Bombay, most of them Jewish, who controlled two-thirds of the trade on the Calcutta exchange…

The Jews hated the rickshaw, which they considered immoral — forcing a man to do the work of a beast. (Pg. 44-46)

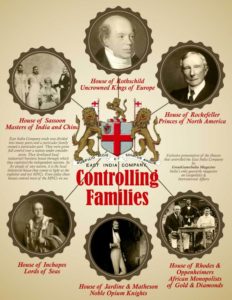

EIC [East India Company] trade as mentioned earlier was divided into many parts and a particular family owned a particular part. For example, the growing of opium and collecting taxes in India was owned by EIC and its paid officials or after 1837 by the British government itself. But the House of Sassoon’s handled the trading in opium and other goods in India. Thereafter, the House of Jardine and Matheson handled their distribution in China and the House of Inchapes handled the shipping of these goods. House of Openheimers/Rhodes handled the gold and diamond mining business. The American operations were handled by the House of Rockefellers, Seagrams, Sassoons, Japhets, Jardine – Mathesons etc. The Houses of Rothschilds and Warburgs coordinated the banking aspect of this trade. Apart from theses, Houses of Lloyds, Abes and Astors assisted these operations by insuring the business of EICs. Even today these houses control most of the MNCS we see. We do an in-depth study of Rothschilds and Rockefellers and at the end give a list of Indian MNCs, only to show how most of these belong to only one single group run by a single family which was associated with the EIC owners, by either business or marriage.

East India Companies had a unique managerial style. In any particular country, all trading, business and commerce was always handed over to one or at the most two business houses. They were given full control over a nation under consideration. From 1800 to 1947, the House of Sassoon controlled most of the trade within India: banking, trading, shipping, insurance etc., from their Mumbai headquarters. Most of them started moving out of India and to England from 1900. Wherever the MNCs were in operation, they followed the above rule. They developed local industrial/business house (India is a large nation so we may encounter multiplicity in case of India), through which they exploited the independent nations.

Christian missionaries allied with the opium traders in China, notes Julia Lovell in her excellent 2015 book, The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern China:

The missionaries became natural allies of the smugglers: when they first arrived on the coast of China, they docked among opium traders on the island of Lintin; they interpreted for them in exchange for passages up the coast, distributing tracts while the drug was taken onshore; and in the Chinese Repository, Canton’s leading English-language publication, they shared a forum for spreading their views on the urgent need to open China, by whatever means necessary. By the 1830s, merchants and missionaries alike favoured violence. ‘[W]hen an opponent supports his argument with physical force, [the Chinese] can be crouching, gentle, and even kind’, observed Karl Gützlaff, a stout Pomeranian missionary who would, during the Opium War, lead the British military occupation of parts of eastern China, running armies of Chinese spies and collaborators. The slightest provocation would do. In 1831, traders had written to the government in India, demanding a fleet of warships to avenge the Chinese authorities’ partial demolition of a front garden that the British had illegally requisitioned…

Opium has been an extraordinary shape-shifter in both the countries that would fight a war in its name in the early 1840s. In Britain and China, it began as a foreign drug (Turkish and Indian, respectively) that was first naturalized during the nineteenth century, then – at the end of that same century – sternly repatriated as an alien poison. For most of the century, neither popular nor expert medical opinion could agree on anything concerning opium, beyond the fact that it relieved pain. Was it more or less harmful than alcohol? Did it bestialize its users? Did it make your lungs go black and crawl with opium-addicted maggots? No one could say for sure. ‘The disaster spread everywhere as the poison flowed into the hinterlands . . . Those fallen into this obsession will ever utterly waste themselves’, mourned one late-Qing smoker, Zhang Changjia, before observing a few pages on, ‘Truly, opium is something that the world cannot do without.’ The clichéd image of opium-smoking is of prostration and narcolepsy; to many (including Thomas de Quincey, who walked the London streets by night sustained by laudanum), it was a stimulant. China’s coolie masses would refresh their capacity for backbreaking labour with midday opium breaks. One reverend in the late-nineteenth century observed that such groups ‘literally live on the opium; it is their meat and drink’. Things were little different in the Victorian Fens: ‘A man who is setting about a hard job takes his [opium] pill as a preliminary,’ wrote one mid-century observer, ‘and many never take their beer without dropping a piece of opium into it’. To add to the confusion about opium’s effects, British commanders in China between 1840 and 1842 noticed that Qing soldiers often prepared themselves for battle by stoking themselves up on the drug: some it calmed; others it excited for the fight ahead; others again, it sent to sleep.

Even now, after far more than a century of modern medicine, much remains unknown about opium’s influence on the human constitution. Whether eaten, drunk or smoked, the drug’s basic effects are the same: its magic ingredient is morphine…

Opium began life in the Chinese empire as an import from the vaguely identified ‘Western regions’ (ancient Greece and Rome, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Persia and Afghanistan); the earliest Chinese reference (in a medical manual) occurs in the first half of the eighth century. Eaten or drunk, prepared in many different ways (ground, boiled, honeyed, infused, mixed with ginger, ginseng, liquorice, vinegar, black plums, ground rice, caterpillar fungus), it served for all kinds of ailments (diarrhoea and dysentery, arthritis, diabetes, malaria, chronic coughs, a weak constitution). By the eleventh century, it was recognized for its recreational, as well as curative uses. ‘It does good to the mouth and to the throat’, observed one satisfied user. ‘I have but to drink a cup of poppy-seed decoction, and I laugh, I am happy.’ ‘It looks like myrrha’, elaborated a court chronicle some four hundred years later. ‘It is dark yellow, soft and sticky like ox glue. It tastes bitter, produces excessive heat and is poisonous . . . It enhances the art of alchemists, sex and court ladies . . . Its price equals that of gold.’9 Opium was supposed to help control ejaculation which, as sexological theory told it, enabled the sperm to retreat to feed the male brain. Opium-enriched aphrodisiacs became a boom industry in Ming China (1368–1644) – possibly contributing to the high death-rate of the dynasty’s emperors (eleven out of a total of sixteen Ming rulers failed to get past their fortieth birthday). In 1958, as part of a final push to root out the narcotic in China, the new Communist government excavated the tomb of Wanli, the hypochondriac (though long-lived) emperor of the late Ming, and found his bones saturated with morphine. Enterprising Ming cooks even tried to stir-fry it, fashioning poppy seeds into curd as a substitute for tofu. Opium was one of the chief ingredients of a Ming-dynasty cure-all, the ‘big golden panacea’ (for use against toothache, athlete’s foot and too much sex), in which the drug was combined with (amongst other things) bezoar, pearl, borneol, musk, rhinoceros horn, antelope horn, catechu, cinnabar, amber, eaglewood, aucklandia root, white sandalwood; all of which had first to be gold-plated, then pulverized, turned into pellets with breast-milk, and finally swallowed with pear juice. (Take one at a time, the pharmacological manuals recommended.)

It was yet another import – in the shape of tobacco from the New World – that led to the smoking of opium. Introduced to China at some point between 1573 and 1627 (around the same time as the peanut, the sweet potato and maize), by the middle of the seventeenth century tobacco-smoking had become an empire-wide habit. As the Qing established itself in China after 1644, the dynasty made nervous attempts to ban it as ‘a crime more heinous even than that of neglecting archery’: smokers and sellers could be fined, whipped and even decapitated. But by around 1726, the regime had given up the empire’s tobacco addiction as a bad job, with great fields of the stuff swaying just beyond the capital’s walls. And somewhere in the early eighteenth century, a new, wonderful discovery had reached China from Java, carried on Chinese ships between the two places: that tobacco was even better if you soaked it first in opium syrup (carried mainly in Portuguese cargoes). First stop for this discovery was the Qing’s new conquest, Taiwan; from there it passed to the mainland’s maritime rim, and then the interior.

It was smoking that made Chinese consumers take properly to opium. Smoking was sociable, skilled and steeped in connoisseurship (with its carved, bejewelled pipes of jade, ivory and tortoiseshell, its silver lamps for heating and tempering the drug, its beautiful red sandalwood couches on which consumers reclined). It was also less likely to kill the consumer than the eaten or drunk version of the drug: around 80–90 per cent of the morphia may have been lost in fumes from the pipe or exhaled. Through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, China made opium-smoking its own: a chic post-prandial; an essential lubricant of the sing-song (prostitution) trade; a must-have hospitality item for all self-respecting hosts; a favourite distraction from the pressures of court life for the emperor and his household. Opium houses could be salubrious, even luxurious institutions, far from the Dickensian den-of-vice stereotype (like an ‘intimate beer-house’, a surprised Somerset Maugham pronounced in 1922 – a mature stage in China’s drug plague), in which companionable groups of friends might enjoy a civilized pipe or two over tea and dim-sum.

Somewhere near the start of the nineteenth century, smokers began to dispense with the diluting presence of tobacco – perhaps because pure opium was more expensive, and therefore more status-laden. Around this time, thanks to the quality control exercised by the diligent rulers of British India (who established a monopoly over opium production in Bengal in 1793), the supply also became more reliable, no longer regularly contaminated by adulterants such as horse dung and sand. A way of burning money, smoking was the perfect act of conspicuous consumption. Every stage was enveloped in lengthy, elaborate, costly ritual: the acquisition of exquisite paraphernalia; the intricacy of learning how to cook and smoke it (softening the dark ball of opium to a dark, caramelized rubber, inserting it into the hole on the roof of the pipe bowl, then drawing slowly, steadily on the pipe to suck the gaseous morphia out); the leisurely doze that followed the narcotic hit. The best families would go one step further in flaunting their affluence, by keeping an opium chef to prepare their pipes for them. The empire’s love affair with opium can be told through the beautiful objects it manufactured for consuming the drug, through the lyrics that aficionados composed to their heavy, treacly object of desire, or in bald statistics…

And today, many Chinese people waste little time fuming over British gunboat diplomacy when left in peace by the state’s patriotic education campaign. Ask Beijing taxi-drivers (an overworked, underpaid labour-force more than entitled to a generalized sense of grievance against the world) what they think of Britain, and you are more likely to get a sigh of admiration (about how modern and developed Britain is, relative to China) than vitriol. Ask them about the Opium War, and they’ll often tell you what’s past is past; they’re too busy thinking about managing in the present (or they don’t listen to anything the government says). Even as secondary-school history textbooks and examinations still strive to indoctrinate young minds with the ‘China as Victim’ account of modern history, always starting with the Opium War, classroom discussions of the Opium War easily lapse out of anger towards the West, and into disgust at nineteenth-century China’s corruption and military weakness. Start a conversation about the Opium War and someone, sooner or later, is bound to come out with the catchphrase luohou jiu yao aida – a social Darwinist sentiment that translates as ‘if you’re backward, you’ll take a beating’; China, in other words, had it coming. Beneath the angry, hate-filled narrative of the Opium War and its aftermath told by Chinese nationalism, then, lies a more intriguing story: that of a painfully self-critical and uncertain, but open-minded quest to make sense of the country’s crisis-ridden last two centuries…

But foreign traders of the early nineteenth century had only a partial role to play: distribution deep into the mainland was carried out by native – Chinese, Manchu, Muslim – smugglers. The clippers sailed up to Lintin, a small, nondescript island about a third of the way between Hong Kong and Canton. There, they discharged their cargo onto superannuated versions of themselves: retired hulks serving as floating depots. Long, slim Chinese smuggling boats – known in the trade as ‘centipedes’, ‘fast crabs’ or ‘scrambling dragons’, and rowed by twenty to seventy thoroughly armed men apiece – would then draw up, into which opium was loaded, to fulfil orders purchased at the factories in Canton. From here, the drug entered the empire’s circulatory system: along the south coast’s threadwork of narrow waterways, and into Canton itself – amid consignments of less contentious goods, under clothes, inside coffins. At every stage, there was employment for locals: for the brokers, couriers and ‘shroffs’ (who checked for counterfeit silver) on board European vessels and in European pay; for the tough Tankas who made the dragons scramble; for the smugglers who brought it ashore; for the Cantonese middlemen; for the proprietors of opium shops, restaurants, tea-houses and brothels.

And every stage in the trade required officialdom to look the other way – which for the most part they obligingly did, even as the traces of the business surrounded them. One of Matheson’s Calcutta associates put it nicely, wondering sarcastically that the agency’s opium clippers ‘have ever been able to trade at all. A European-rigged vessel gives the alarm against herself whenever she appears, and lodges an information in the hands of every individual . . . Only think of the Chinese going to smuggle tea on the coast of England in a junk!’ Generally, all that was required to land opium was cash outlay and sometimes a touch of doublespeak. If an opium consignee was lucky, the responsible mandarin would simply demand a businesslike bribe per box of opium – like a species of duty, as if the cargo were nothing more controversial than cotton, or molasses. If he were less fortunate, he would suffer a lecture administered first on the evils of the opium trade, or perhaps a personal reading of the emperor’s latest edict on the subject, then be allowed to hand over the bribe. But connivance – because of the profit to be made from it – seems to have been the basic rule: one exploratory trade mission by the EIC up the north China coast in 1832 was greeted by disappointment all the way, as the ship, the Lord Amherst, had neglected to bring opium…

When – and only when – the clippers were safely unloaded and preparing to return to India, Qing government ships would, one sardonic observer of the mid-1830s noted, at last mount a sham pursuit: ‘twenty or thirty Chinese men-o-war junks are seen creeping slowly . . . towards them . . . never close enough to be within reach of a cannonball, and if, for the sake of a joke, one of the clippers heaves to, in order to allow them to come up, they never accept the invitation, but keep at a respectful distance . . . a proclamation is [then] issued to the entire nation, stating that “His Celestial Majesty’s Imperial fleet, after a desperate conflict, has made the Fan-quis [foreign devils] run before it, and given them such a drubbing, that they will never dare show themselves on the coast again.”’ Thus, summarized an American trader of the 1830s, ‘we pursued the evil tenor of our ways with supreme indifference, took care of our business, pulled boats, walked, dined well, and so the years rolled by as happily as possible.’

…When the Communist Party – while publicly denouncing their rivals, the Nationalists, and Western imperialists for profiting from the drug trade – secretly grew opium to make ends meet in north-west China in the early 1940s, they generated another couple of euphemisms: ‘special product’, and sometimes ‘soap’.

By the time of the Opium War, the empire was not just importing and domesticating this prized foreign drug; it was producing it, in tremendous quantities. (Nonetheless, although native opium appealed because of its cheapness, it was always a poor cousin to the foreign product, due to the greater potency of the latter.) Where it grew readily (especially in southwest China, but also along the east coast, and in Shaanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang to the north-west), it was the wonder crop: it sold well, and grew on the same land in an annual cycle alongside cotton, beans, maize and rice. Almost every part of the plant could be used: the sap, for raw opium; the leaves as a vegetable; the stem for dye; the seeds for oil. For southern peasants in the late 1830s, growing opium earned them ten times more than rice. By the time of the Opium War, the trade had spread across the entire empire: smoked (extensively) in prosperous south-eastern metropolises; trafficked; and cultivated (all along the western rim, from the mountain wildernesses of Yunnan in the south, to Xinjiang in the north).

Opium simply refused to go away: when the state moved to crack down on opium along the south and east coast by banishing smokers and smugglers to the frontier zone of Xinjiang, they merely brought their habit to the north-west. If domestic poppy-growing was cut back in south-western provinces such as Yunnan, civil servants predicted that coastal imports would increase to fill the market space made available. In 1835, officials optimistically announced that the poppy had been eradicated from Zhejiang, in east China; five years later, further investigation revealed that government representatives had lopped only the tops of the plants, carelessly leaving the roots still in the ground. That same year, thirty-four peasants fought officials sent to destroy their crops properly…

But why did the Qing fail to capitalize on their numerical superiority over the British? Theoretically, the dynasty commanded the largest standing army (800,000-strong) in the world at the time – 114 times more numerous than the 7,000-strong British force dispatched to China. In reality, however, most of these 800,000 soldiers were scattered through the empire, far too busy with domestic peace-keeping duties (suppressing bandits or rebels; carrying out disaster relief; guarding prisons; policing smugglers) to be spared for the quarrel with the British. In August 1840, when the British fleet glided up to Tianjin, to hand Palmerston’s official letter of complaint to the emperor, the imperial representative reported that a mere 600 of the 2,400 soldiers theoretically on the rolls could be mustered for immediate service. Almost every province of the empire had to contribute reinforcements to boost local forces: in the course of the war, some 51,000 soldiers found themselves in transit around the country, headed for the southern or eastern coasts. But they moved too slowly to be useful: troops from a neighbouring province took thirty to forty days to reach the front line (about the same amount of time it took the British to fetch reinforcements from India); those further away took ninety or more. In June 1840, the British fleet took only thirty-five days to sail up and capture Dinghai; the following year, the Qing took five months to rally a counter-offensive against the island – five months in which the British rested and reorganized, while reinforcements straggled in from distant corners of the empire. (By the time the last batches arrived, the Treaty of Nanjing was already being toasted in cherry brandy.)

…Military discipline was another problem for the Qing. British accounts of Opium War engagements were scattered with admissions that forts were adequately planned, placed and supplied, and would have cost the invaders many lives to capture – if only the Qing troops had fought, and not fled. The conquest of the empire had been achieved by creating a hereditary military: an elite minority of Manchu, Mongolian and Chinese Bannermen at the top, with the professional Chinese Green Standard Army (about three times the size) taking on basic garrison duties through the country. For the Bannermen, the state provided a stipend of rice, cash and land, in return for army service. But by the middle decades of the eighteenth century, the Banners were suffering from price rises just like everyone else in the empire – the level of stipends had been set in the early years of the conquest, long before the inflation of the Qianlong period set in. When handouts failed to keep up with inflation, or even shrank, soldiers protested, went on strike, ran away or took civilian jobs. As the nineteenth century approached, the system was rotten with corruption: superiors squeezed inferiors in exchange for the promise of promotion, while families concealed deaths (and invented births) to maintain stipends.

Equipment budgets and military esprit de corps were the principal casualties of the fiscal deficit. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, musketry and artillery practice were phased out across many garrisons, because ammunition was too dear. One of the east-coast garrisons in 1795 requested permission from the Board of War to cancel the spring artillery practice, for fear that the noise would disturb the well-being of profitable silk worms; so much grazing land had been sold or rented out that the number of horses dwindled to almost nothing. In the Canton garrison, half-naked Manchus on drill practice were observed dragging rusty swords and elderly bows about…

Repeatedly during the war, Qing armies of thousands would be routed by a few hundred, or even a few dozen well-disciplined British troops with functioning artillery and battle-plans.

During the Opium War, Qing politicians of the pro- and anti-war faction could agree on only one thing: that their army was hopeless. Travelling east from Canton to Zhejiang in 1841, Lin Zexu bluntly analysed the reasons for the army’s lack of interest in fighting the British. ‘The most coveted positions in the Guangdong garrisons were in the naval fleet, where one per cent of salaries was drawn from the grain and silver stipend, and the rest from opium-smugglers’ bribes. Once we banned opium, ninety-nine per cent of the navy’s income went up in smoke. How could we expect them to resist the English rebels?’ ‘Our soldiers cheat everyone’, echoed Qiying, the emperor’s chief negotiator at the close of the war. ‘They refuse to pay full prices, gather in brothels and gambling dens, corrupt the sons of good families and handle stolen goods.

…Bao Peng, this opium-smuggler turned imperial diplomat, offered a particularly colourful example of Chinese collaboration with the British, but he was only one of many who betrayed the Qing by helping the empire’s attackers: not out of conscious ideological choice, but simply because they needed to make a living, and the British were employers like any other.

According to both English and Chinese sources, locals defected back and forth between the two sides depending on which offered them the most reliable source of income. After the opium trade dried up in the late 1830s, those who had drawn a living from transporting, unpacking, supplying and peddling were recruited (at the wage of six dollars a month) into anti-British defence militias – a strategy that Lin Zexu described as ‘fighting traitors with traitors, poison with poison’. When these bands were disbanded in late 1840 as part of the ‘soothing’ process, their members quickly changed sides again. ‘Once they found themselves unemployed,’ recalled one Cantonese observer, ‘they took to wandering up and down the coast. The foreigners relied on two of their dastardly leaders, who incited others to go over too . . . Without this help, the British would not have known anything – this was how Charles Elliot found out how slack the defences leading up to Canton were.’ When the British fleet returned to the south, seasoned Cantonese boatmen offered their services to the British, with all the importunate matter-of-factness of taxi drivers touting for trade outside a railway station. ‘How four-piece ship no wanchee pilot’, one local navigator shook his head, on being rejected.8 Everywhere the British went, they were dependent on local willingness to provide them with fresh food and water. When the Elliots returned south in late November 1840, and docked their fleet on the eastern side of the mouth of the river up to Canton, a floating Chinese township kept them well supplied with fresh food, even at the risk of persecution by officials. When the names of this impromptu comprador community were taken down by a group of police spies, the businessmen besieged and set fire to the police boat. ‘These poor wretches were literally roasted alive, their persecutors preventing their escape with long bamboos’, recalled an English lieutenant. ‘What a most extraordinary nation this is! … They will trade with you at one spot, while you are fighting, killing and destroying them at another!’

…Just as at Zhapu a month of so earlier, or at Sanyuanli the previous year, the only effective opposition to the British in the Opium War fought not for patriotism or even profit, but for their own women and children. As they died inside the city, the Bannermen may have wondered why no reinforcements from the camps to the west of the city were coming to their aid. These troops from western and central China had fled south at the first exchange of fire with Britain – this was not their fight. The casualty statistics for the day tell the story well enough. 30 per cent of the garrison’s resident Banner troops died on 21 July, while only 1.6 per cent of the Chinese reinforcements from Hubei, Sichuan, Henan and Jiangxi lost their lives. The war was, British observers now noted, ‘a Manchu and not a Chinese affair.’ And once the Manchus were laid low by the British, their persecuted Chinese subjects took vengeful advantage of their disarray. After Zhapu, British intelligence officers observed, ‘the Chinese populace fell upon the helpless families [of Manchu soldiers], committed every enormity and carried off every moveable article worth taking.’ (Reprisal, perhaps, for the Qing army’s own brutality against civilian Chinese populations in previous decades’ suppressions of religious rebellions – which had left tens of thousands dead.) In Zhapu, at least two separate accounts claimed, the Manchus had so badly antagonized Chinese soldiers that the latter became fifth-columnists for the British: ‘As the Manchu garrison had been in the habit of calling the Chinese disloyal, the Fujian braves sided with the enemy and set fire to the town. The foreigners then scrambled in over the wall’.

Even as desperate struggles went on inside and around the city, many of those removed from the front line carried on with their lives, apparently unconcerned about what might be happening to their compatriots a few hundred yards away. To reach the city, Granville Loch and his column – under and returning fire – had to cross a village in easy sight of Zhenjiang. Far from escaping the theatre of war, its inhabitants were standing, spectating, in the streets, ‘coolly employed eating their bowls of rice . . . although they were viewing a contest between foreigners and their fellow-countrymen, and in danger themselves, from their position, of being shot’.

…Up to this point, Yan Fu’s education and career – with its loyalty to Chinese tradition and dedication to modern military science – bear passing resemblance to Rohmer’s paranoid hypotheses about ambitious Orientals conspiring to beat the West at its own game. But here, Yan’s life story departs from the Yellow Peril narrative. His decision to study Western science was not part of a grand, premeditated scheme – it sprang from economic necessity. After his father died when Yan was thirteen, the family finally abandoned all hope of supporting the boy through studying for the civil-service exams – in later life, Yan Fu recalled how his mother toiled at needlework to keep the family fed and clothed, and how he would be woken through the night by the sound of her weeping. The Fuzhou Shipyard, by contrast, could offer attractive incentives: free board and lodging, and a stipend of four silver dollars a month (with a bonus of ten silver dollars to students who came top in the quarterly exams).

The bribery was necessary, for in late-nineteenth-century China a Western education remained a disreputable life choice. ‘Only the truly desperate stooped to studying Western sciences’, remembered the writer Lu Xun, who took classes in medicine at one of the east-coast academies in the 1890s. ‘By following the course I had fixed upon, I would be selling my soul to foreign devils’. To praise the modernity of Western methods, to seek employment in the new Qing Foreign Office or (even more unthinkably) in an embassy abroad, was to court career catastrophe. Guo Songtao, the Qing ambassador to London during Yan Fu’s time in Britain, was a case in point. For his pro-Western views, he was physically assaulted, multiply impeached and eventually dismissed and sidelined from politics, while his house in China was vandalized. ‘The empire cold-shoulders him’, ran one contemporary scrap of doggerel. ‘He cannot serve human beings / So how can he serve demons?’

Secondly, Yan Fu had little interest in waging war on the white race. Quite the opposite: through his study of science and English, he fell in love with the West – and not just with the iron-plated steamers and guns that he was supposed to be studying, but also with its thinkers, writers and political and legal institutions. This, Yan concluded during his years abroad, was the foundation of Western strength. ‘The reason why England and the other countries of Europe are wealthy and strong is that impartial justice is daily extended’, he declared to Guo, during one of their Sunday conversations. ‘Here is the ultimate source.’ Yan Fu remains a celebrity in China today for a remarkable series of translations that he completed after his return from England: Smith’s Wealth of Nations, J. S. Mill’s On Liberty, Montesquieu’s L’Esprit des Lois. Yan Fu sought an idiom that would convince China’s educated elites of the profundity of Western thought, rendering canonical texts of the modern West in the pure classical Chinese of the first millennium BC. ‘The books with which I concern myself are profound and abstruse’, Yan Fu reasoned. ‘They are not designed to nourish schoolboys’. But he is famed also as a leading representative of the first generation of Chinese men after the Opium Wars to launch upon a pointedly introspective quest – one of the country’s key intellectual shifts of the nineteenth century – to understand China’s weakness, and Western strength.

In their long discussions in London, Yan Fu and Ambassador Guo whiled away the hours assessing the virtues of the West and bemoaning the sins of China and the Chinese. For according to his diary, Guo shared with Yan Fu an extravagantly high opinion of China’s imperialist adversaries (and of Great Britain in particular) – a fact that was all the more extraordinary given the discourteous reception that he received in Britain. On his arrival in London, Punch ran a cartoon and seven poetic stanzas of impeccable offensiveness, in which Guo was caricatured as a monkey (‘With his eyes aslant, and his pigtail’s braid / Coiled neatly round his close-shaved head . . . As stubborn as pigs and as hard to steer / With a taste for cheap buying and selling dear’), peering at the stately lion of the British empire. A week later, the magazine devoted a whole page of tasteless doggerel to the bound feet of Guo’s wife, whom it christened ‘the tottering Lily’ and depicted as a décolleté Geisha.

Yet Guo’s enthusiasm was undented. Even on his voyage to England, during which he suffered constant discomfort (in addition to seasickness, he was afflicted by a sore throat, laboured breathing, dizziness, swollen gums, toothache, a smarting nose and heart pain), he sportingly retained an appreciation for everything Western that he saw: the Europeans’ ‘ceremonial

courtesies’ he found ‘refined and civilised’, their navigational techniques extraordinarily commendable. ‘That country certainly produces admirably talented men’, he remarked, observing German officers seeking exercise in a game of leapfrog. ‘Admirable!’9 Given Great Britain’s not particularly creditable record in China, Guo also took a surprisingly positive view of its long-term intentions towards his country. The British have, he considered, ‘surrounded China and press close upon

her:“With their hands reaching high and their feet travelling far, they rise up like eagles and glare like tigers . . . Yet for all this, they have not the slightest intention of presuming on their military strength to act violently or rapaciously . . . the nations of Europe do have insight into what is essential and what is not and possess a Way of their own which assists them in the acquisition of wealth and power . . . Their governmental and educational systems are well-ordered, enlightened and methodical.”

If Great Britain and the West were a repository of all that was worth emulating, the (in Guo’s view) stupid, smug Chinese were by contrast a source of disgust. ‘Surely this is not the time for China to indulge in highflown talk and vain boasting in order to aggrandise herself!’ he sighed on the subject of anti-European prejudice. ‘After thirty years of foreign relations, our provincial authorities still know nothing . . . The weakening of the Song and the downfall of the Ming, were both the outcome of the actions of such irresponsible and ignorant people.’

…Even as opium remained a Chinese aspirin for the under-medicated masses, a fuel (as stimulant and appetite suppressant) for armies of cheap labour and a pleasure-giving narcotic for those with money and leisure, elite moral opinion was starting to move against the drug.

[…]

In the first decade of the twentieth century, in cities and towns across the country, opium-suppression societies denounced the drug in parades, meetings, journals and pamphlets. Hundreds of thousands of dens were shut down, while crowds gathered to attend burnings of confiscated opium and pipes. Investigators raided suspected illicit dens by night; vigilantes set upon inveterate smokers.

[…]

The truly unfortunate were locked up, abruptly deprived of the drug and dosed with strong coffee. ‘Opium took us to paradise’, scrawled one unfortunate on the wall of a late-nineteenth-century clinic. ‘Now we are tortured in hell.’ Those too poor or overworked to find an alternative, one missionary reported, simply died of the shock: ‘When the opium dens were first closed the mortality among the poorer people was dreadful, for the opium smokers lived from hand to mouth, and, as they could not work without their usual opium, they died, partly of starvation, and partly from sudden deprivation of the drug.’

[…]

In a province like Sichuan, in any case, locals had some difficulty in viewing opium as a foreign commodity, because local production had long outstripped imports. Since 1860, opium duties had bought boats, guns and ammunition to help the Qing government suppress civil wars such as the Taiping Rebellion. After 1874, Li Hongzhang had argued that domestic cultivation should openly resume, while piously declaring that the ‘single aim of my Government in taxing opium will be in the future, as it has always been in the past, to repress the traffic – never the desire to gain revenue from such a source.’ Nonetheless, during the 1870s south-west China alone began to produce more opium than the country was importing. Anti-imperialist passions in late-Qing China were often directed at issues other than opium. Through the 1900s, many regions of China were in the grip of a passionate Rights Recovery Movement, opposing European and American attempts to buy up the country’s nascent railway system and Qing willingness to sell it: students threatened to starve themselves to death, soldiers wrote letters of protest in blood and one academic allegedly died of sadness on hearing the news that the government had accepted a massive foreign loan to build one stretch of track.

[…]

And despite the anti-opium fury generated across the fin-de-siècle empire, plenty of people seemed unable to make up their minds about it or to treat it as a serious problem. The inconsistency of Sun Yat-sen, acclaimed on both sides of the Taiwanese straits as guofu (the father of the modern Chinese nation), was exemplary. ‘Opium has caused more harm than war, plague and famine in China for more than ten years’, he pronounced in the 1920s, perhaps forgetting that back in 1894 he had advised the Qing leadership to exhort the people to grow their own poppies to squeeze out the foreign competition, informing them that he had enjoyed much success persuading farmers in his home village in Guangdong to do just that. The bouquet of his local variety, he commented with authority, was ‘even better than that of Indian opium, and far superior to that of Sichuan and Yunnan.’ Shanghai guidebooks vacillated over opium, exclaiming on one page about the wonders of the city’s opium halls, while attacking the drug as a poison on another.

[…]

But our best example of early twentieth-century China’s ambivalence towards opium is perhaps Yan Fu. Aged twenty-eight, he acquired – to the tremendous disappointment of his later nationalist biographers – the opium habit himself, thirteen years before he would begin to characterize it as one of China’s most pernicious customs. He struggled guiltily with the habit for the rest of his life – even though his breathing problems gave him a sound medical reason for taking the drug as a cough suppressant. In 1921, a year after he had finally succeeded in giving up his opium pipe, he died of asthma.

…In Nationalist declarations, opium was legally and morally beyond the pale: in 1928, Chiang’s new government announced a ‘total prohibition’ (juedui jinyan). Unofficially, however, the Nationalists – like the warlord regimes they fought through the 1920s and 1930s – needed the opium trade for revenue. Between 1927 and 1937, the Nationalist government strove (often with surprising success, given appalling obstacles such as Japanese invasion and worldwide depression) to transform an impoverished, fragmented country into a modern unified state: creating national ministries, commissions, academies; building roads, railways, industries, dams. In the absence of crucial resources such as income tax, opium duties would have to do instead. For the creative tax-collector – and Republican China was full of them – there was a wealth of surcharges to be extracted from opium: in duties on the drug itself (plus its transport and retail); and licences to sell and smoke it. The state even maintained a monopoly on opium-addiction cures. The citizens of the republic dodged these taxes with comparable ingenuity: one filial individual smuggled opium between west and east China by concealing it not just inside his father’s coffin, but inside his father’s skull inside the coffin.In 1928, drug revenues helped keep the country’s armies – at a total of 2.2 million, the largest in the world (costing $800 million a year) – standing. A 1931 cartoon entitled ‘Shanghai business’ pictured three figures: to left and right two dwarfs labelled ‘industry’ looked skyward at the towering colossus between them – Opium. In 1933, the size of the opium traffic in China was estimated at $2 billion annually (5.2 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product). In many regions and contexts, opium was as good as, if not better than, money, and an essential commercial and social lubricant – ‘light the lamps’ was standard Chinese for ‘let’s talk business’; opium pipes were offered at weddings as conventionally as wine. The country literally reeked of the stuff, thanks to the vats of the drug publicly boiled in the streets of towns and cities: by the 1930s, China may have had as many as 50 million smokers (around 9 per cent of the population).

[…]

In the meantime, the Nationalist government identified offices for collecting opium tax as ‘opium suppression bureaus’, while opium merchant guilds could be euphemistically labelled ‘medicinal merchants’ friendship associations’.54 ‘Millions have been raised out of opium’, remarked the International Anti-Opium Association in 1928. ‘Nationalist Government monopolies exist in every large centre, and are so efficiently organised that enormous revenues result. And although the evil of the so-called “Opium Wars” has invariably been referred to on every Nationalist platform and in every proletarian demonstration, the Government is raising the very last cent out of the cultivation and use of opium.’ Not for nothing did the Cantonese have the saying, ‘Opium addiction is easy to cure; opium tax addiction far harder.’

Anti-opium activists reviled the government’s pragmatic efforts to generate useful, state-building money out of the drug: ‘As we look around at the conditions within China, opium is everywhere, how sickening! HOW SICKENING! We truly hope that the government authorities will . . . completely prohibit opium, and earnestly eradicate it in order to save the tarnished reputation of our country and forever consolidate the foundation of this nation.’ The government gave earnest public pledges that it ‘will absolutely not derive one copper from opium revenue. If anything of this sort is suspected . . . we can regard this government as bankrupt and place no confidence in it.’ ‘If we want to save China,’ Chiang Kai-shek added, ‘we must begin with prohibiting opium, and that prohibition must begin with the highest echelons of the leadership . . . Prohibit the poison if you want to save the country, the people, yourself, your sons and grand-sons.’ ‘The opium evil’, he explained elsewhere, ‘constitutes a greater menace to the nation than foreign aggression, because the former leads to self-degeneration and self-suicide, whereas the latter is invited by mutual dissension, weakness and degeneracy.’ In private, the regime did its best to silence inconvenient opponents by frightening off their sponsors, by smearing them with accusations of drug-smuggling, by sending them death threats; or simply by planting bombs in their houses. In 1931, the government was buffeted by one of its biggest drug scandals, when a group of Shanghai constables intercepted an opium shipment that a company of Nationalist soldiers were busy unloading. The men of the law were promptly taken prisoner until the precious drug had found its way to its gangland destination.

[…]

For decades, Communist propaganda held that the Maoists worked their way out of their predicament through frugality and popular democracy (by introducing rent reduction and cooperative farming practices), until a historian called Chen Yung-fa noticed at the end of the 1980s that account books for the period were scattered with references to a ‘special product’ that rescued the Communists from their trade deficit of the early 1940s and that, by 1945, was generating more than 40 per cent of the state’s budget. A little more detective work revealed that this was opium, processed in ‘Special Factories’ and transported south and west to generate export revenue for Communist armies. (‘Since opium entered China’, a Communist editorial of 1941 explained, ‘it has become the greatest source of harm to the Chinese people, inseparable from imperialist invasion . . . Imperialism has used opium to enslave and oppress the Chinese people. As the Chinese people have become ever weaker, ever poorer, opium has played a most detestable and poisonous destructive role.’86) But in 1945, as an American mission flew in to inspect Mao’s kingdom, it found itself gazing over nothing more controversial than swaying fields of sorghum and wheat. The opium poppies had been uprooted just in time to maintain – for the next forty years at least – the propriety of the Chinese Communist wartime image.

A Chinese blogger in Sinagpore (with a background in Christianity) says:

This is why I will never understand the pathological self-loathing of the West. I mean, come on, with your persistent self-flagellation you’re just asking to be taken advantage of and of course the Chinese are experts of emotional blackmail. The minute you try to criticise us we’ll drag every tiny infraction from ten thousand years ago to shut you down. Seriously man…

What justifies other world powers’ attempt to destroy the ISIS? If one simply says that that’s because they persecute Christians within their land and that we must make the land free for the spread of the Gospel, then this would also justify the British blasting open China to allow their missionaries to enter and enable the free spread of the Gospel. If we want to go by the logic of leaving China alone even if they don’t allow Christianity within her, wouldn’t the same logic apply to the ISIS as well, and that the fact that they don’t allow Christianity in their midst is no justification for trying to wipe them out?

If one says that the ISIS are persecuting pre-existing Christians who are already there then the obvious solution would be to evacuate them and not to instigate regime change. So what really justifies our destroying the ISIS? The fact that they have horrible practices? Doesn’t Saudi Arabia have them as well? But that doesn’t justify us trying to level them.

In the end, I do not know what the answer is here. Here I invoke my moral particularist/nihilist credentials and simply fall silent. However I think I can say with a reasonable amount of confidence that if Britain did not blast open China, Christianity would be as extinct in China as it would be in Japan, virtually a tiny minority spreading at snail’s pace. For good or bad, the British forcing China open to the West has allowed Christianity to flourish there today. As a Chinese, I choose to enjoy the side benefits of the Opium War, and leave the judgement of the actors to God.

…we’re not annoyed that the British smuggled opium in China but that they managed to do it more effectively than us and for a larger cut of the profits.

For regardless of the “official” position of both the British and Chinese government on the opium trade, at the local level the peoples on both sides were more than happy to profit from it.

This honestly reminds me a lot of why we are annoyed with the Americans. It isn’t that they were more treacherous or immoral than the rest of us. It’s simply that they tend to engage in more insufferable moral posturing which makes the dissonance of their less than perfect behaviour irritating. Likewise the pathological self-loathing of the West and the British with regards the opium trade is simply because they have a much higher opinion of their own moral standards and treat their “fall” from it with greater loathing and disgust. The rest of us merely have a much more lower and pragmatic attitude towards morality which is why our no less dastardly deeds gets a free pass while the West gets the endless blame of the academia…

We take covering up a bribe to the nth degree with an elaborate spectacle to boot. It might have something to do with the way we are able to compartmentalise our minds and maintain many faces at once. I guess this is why I’ve never taken moral posturings or outrageous seriously. Being Chinese, moral posturing is normally a theatrical act invoked to disguise our true motives or to accomplish some very specific agendas. I prefer to simply objectively observe facts without feeling the need to indulge in pretentious moral posturing…

Perhaps the Chinese Legalist thinking of Han Feizi does run deeper in the Chinese psyche than we would care to admit. Our “might is right” attitude of selling our services to whoever is the most powerful, our pursuit of self-interest and disregard for macro-political or national loyalties and forces, etc…

Sigh, I am starting to see why the Chinese themselves believed that we deserve to get beaten during the Opium War. It was a foolish and utterly unnecessary war if the Emperor had exercised a little bit more pragmatism towards the British. Sometimes it may really be better to be ruled by foreigners than to be protected by one’s “own” idiots. This book is causing me to re-evaluate my recent more sympathetic attitude towards China.

Pax Britannica may not be that bad an idea after all…

To be honest, this is an incredibly depressing book to me personally. As much as I may have ranted against Confucian hypocritical moral posturing, but our race takes spin, lying, and sheer deception to a whole new level. With one side of our mouths we lecture the West about their opium trade with the other side we discreetly give orders for their taxation and farming.

I feel the last vestiges of my recent sinophilia dying with this book, and perhaps along with it any remaining belief in strong authoritarian nation-states. Reading about the futile wars for the reunification of China and the lengths of hypocrisy which people will go to to make it happen, I cannot help but wonder whether the British had a good point about localism after all.

It is my incredible good fortune or divine mercy for me to have been born a Singaporean where English rule of law and fair play is respected.

I will need to think very carefully the implications of this book in the days to come. Perhaps it would be a mercy for God to wipe out the very idea of the Chinese race itself and have us all assimilated into the West…

One of the more interesting insights to come out of the book is that while the Chinese would naturally blamed the foreign devils for their unjust invasion, the Chinese would in fact blame themselves more than the foreigners. There is a sort of self-loathing to the point of pathological in Chinese reflections on the topic whereby they blamed their own backwardness, their own moral weakness, their outdated political systems, science or philosophy, etc, for their defeat by the Western imperialists.

Consciousness of these facts has generated a very dialectical to the point of contradictory love-hate relationship between the Chinese and the West. On the one hand, the West are loathed for their invasion and humiliation of China, on the other hand they must have gotten something right which is precisely why they could beat us, leading to the need for us to emulate and copy their ways that we might partake of their strength and success. Lovell notes in her book the ironic posture of fervent young Chinese nationalists who would swear at the British at one moment and then ask her how might one go about studying in Britain at the next.

The trade that made Sassoon a multi-millionaire was opium, grown in India and shipped east to China…

Opium was introduced in China as a medical treatment in the 8th century by the Arabs. In 1793 British East India Company secured a monopoly whereby it would be the only company allowed to sell opium produced in India’s fields, most of which was then sold into China.

Opium became the single most valuable commodity of the entire 19th century. This monopoly was broken in the 1830’s when other British companies such as Jardine Matheson as well as Parsi, Arab and Jewish traders were able to get into the opium trade. British firms began to withdraw from the market as competition ate into their profits.

In the 1890’s Singapore’s Jewish merchants began reinvesting their profits in stocks and property. By the end of the 19th century the Jewish merchants had long been well out of the opium business.

The traders were Orthodox Jews.

I initially found only one book on the family — Sassoons by Stanley Jackson, published in 1968:

The first Sassoon arrived in China in 1844. He was David’s second son, Elias, who decided that Shanghai and Hong Kong offered by far the best prospects for opium and textiles…

Like most other wealthy Jews of Persian or Mesopotamian origin, the Sassoons kept a number of slaves bought from Arabic-speaking tribes.

…no Jewish beggar would ever be seen in the streets of Bombay…

[David Sassoon] endowed almost a miniature ‘welfare state’ for his co-religionists…

This was harvest time for David Sassoon & Sns. The Yangtse mud glinted with gold as soon as they laid a brick on it. It was the same in all the Treaty Ports where land values bounded from year to year. Their wharves and godowns were bursting with opiums, cotton goods, silks, spices, tea and metals… Scores of junk masters along the China coast were now…permanently on their payroll…

The Sassoons had an easier passage to royal favour [with England’s Queen Victoria]. They were admirably poised to make the best of both worlds. They profited by their friendships with the Rothschilds, yet enjoyed more immunity from the snobbery and racial prejudice that persisted towards that clan… Opium trading was still considered unexceptionable and apparently less noxious socially than vulgar profit-making on the Stock Exchange.

Then I found, “Jews, Opium and the Kimono: Story of the Jews in the Far East” by Ezra Yehezkel-Shaked. One description says: “RARE book on the central role the Jewish people played in the Far East countries, such as building Shanghai and Hong Kong, helping creating the Chinese Army, introducing Communism to the Chinese people, arming the Japanese forces in their war against Russia (1904-05), discovering in Bombay and spreading the vaccine against cholera and the plague throughout the Far East…”

David Sasson has been memorably and accurately described as “the greatest Drugs Kingpin in the history of the world” [1] but official histories do their level best to obfuscate his dominant involvement in the opium trade which was the major source of his wealth. Sassoon was a pivotal figure in both the trading regime of the British Raj and British Subjugation of China in the first “Opium War” of 1839-41, but in spite of this, he does not have an entry in Encyclopedia Britannica. Similarly the Wikipedia entry has been sanitised over the years to remove all reference to his instigation of the “Opium Wars” [2]; the Jewish encyclopedia devotes two thirds of its entry to his philanthropy [3]

He is justifiably best known for monopolizing the opium trade into China and encouraging its use there. He was born in Baghdad into a family of Nasis, traditional leaders of the Jewish community. His father, Saleh Sassoon, was a wealthy banker and chief treasurer to the pashas, the governors of Baghdad, from 1781 to 1817. However, the Jews came under pressure from the Muslim Turkish rulers of Baghdad. Fleeing with his wife and family and a small part of the family’s wealth, Sassoon arrived in Bombay in 1833.

He started business in Bombay with a counting house, a small carpet godown, and an opium business. He was soon one of the richest men in Bombay. He chose to follow the market, but he pursued all his enterprises better than his chief rivals, the Parsis. By the end of the 1850s, it was said of him that “silver and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium and cotton, wool and wheat – whatever moves over sea or land feels the hand or bears the mark of Sassoon and Company”…In Bombay, David Sassoon established the house of David Sassoon & Co., with branches at Calcutta, Shanghai, Canton and Hong Kong. His business, which included a monopoly of the opium trade in China, (even though opium was banned in China) extended as far as Yokohama, Nagasaki, and other cities in Japan.

In 1836, the opium trade reached over 30,000 chests per annum and drug addiction in coastal cities became endemic. In 1839, the Manchu Emperor ordered that the opium smuggling be stopped. He named the Commissioner of Canton, Lin Tse-hsu, to lead a campaign against opium. Lin seized and destroyed 2,000 chests of Sassoon opium. An outraged David Sassoon demanded that China compensate for the seizure or Great Britain retaliate.…David Sassoon was conscious of his role as a leader of the Jewish community in Bombay. He helped to arouse a sense of Jewish identity amongst the Bene Israeli and Cochin Jewish communities. The Sassoon Docks (built by his son) and the David Sassoon Library are named after him. He also built a synagogue in Byculla.