Here are some highlights from this 2010 book (and here are maps of national cultures on six dimensions):

* 11th juror: (rising) “I beg pardon, in discussing . . .”

10th juror: (interrupting and mimicking) “I beg pardon. What are you so goddam polite about?”

11th juror: (looking straight at the 10th juror) “For the same reason you’re not. It’s the way I was brought up.”

—Reginald Rose, Twelve Angry Men

Twelve Angry Men is an American theater piece that became a famous motion picture, starring Henry Fonda. The play was published in 1955. The scene consists of the jury room of a New York court of law. Twelve jury members who never met before have to decide unanimously on the guilt or innocence of a boy from a slum area, accused of murder. The quote cited is from the second and final act when emotions have reached the boiling point. It is a confrontation between the tenth juror, a garage owner, and the eleventh juror, a European-born, probably Austrian, watchmaker. The tenth juror is irritated by what he sees as the excessively polite manners of the other man. But the watchmaker cannot behave otherwise. Even after many years in his new home country, he still behaves the way he was raised. He carries within himself an indelible pattern of behavior.

* The core of culture according to Figure 1.2 is formed by values. Values are broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others. Values are feelings with an added arrow indicating a plus and a minus side. They deal with pairings such as the following:

■ Evil versus good

■ Dirty versus clean

■ Dangerous versus safe

■ Forbidden versus permitted

■ Decent versus indecent

■ Moral versus immoral

■ Ugly versus beautiful

■ Unnatural versus natural

■ Abnormal versus normal

■ Paradoxical versus logical

■ Irrational versus rational

Figure 1.3 pictures when and where we acquire our values and practices. Our values are acquired early in our lives. Compared with most other creatures, humans at birth are very incompletely equipped for survival. Fortunately, our human physiology provides us with a receptive period of some ten to twelve years, a span in which we can quickly and largely unconsciously absorb necessary information from our environment. This includes symbols (such as language), heroes (such as our parents), and rituals (such as toilet training), and, most important, it includes our basic values.

* From 1940 to 1945, during World War II, Germany occupied the Netherlands. In April 1945, German troops withdrew in disorder, confi scating many bicycles from the Dutch population. In April 2009, the Parish Council of the Saint-Catharina church in the Dutch town of Nijkerk received a letter from a former German soldier who, on his flight to Germany from the advancing Canadians, had taken a bike that was parked in front of the church. The letter’s author wished to make amends and asked the Parish Council to trace the owner or his heirs, in order to refund the injured party for the damage.

* Religious sects tend to draw their moral circle around members of their own community. Moral rights and duties, as well as rewards in the afterlife, are granted only to members of the faith. Religion, in essence and whatever the specific beliefs of a particular one, plays an important role in creating and delineating moral circles. Nations and religions can come into competition if they both attempt to delineate a society-level moral circle in the same country. This has frequently happened during our history, and it is still happening today. The violence of these conflicts testifies to the importance of belonging to a moral circle. It also shows how great a prerogative it is to be the one who defines its boundaries. Through visits and speeches, new leaders typically take action to redefine the boundaries of the moral circle that they lead. Some societies and religions have a tendency to expand the moral circle and to consider all humans as belonging to a single moral community. Hence the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,11 and hence calls for development aid. Indeed, animals can be drawn into the moral circle: people form associations or even political parties to protect animal rights, and pet animals are solemnly buried. However, in such a vast moral circle, rights and duties are necessarily diluted. Historically, religions that were tolerant of religious diversity have lost out against those that were more closed on themselves. Most empires have disintegrated from the inside.

* Gert Jan once took a night train from Vienna to Amsterdam. An elderly Austrian lady shared his compartment and offered him some delicious homegrown apricots. Then a good-looking young black man entered. The lady seemed terrified to find herself within touching distance of a black man, and Gert Jan set to work trying to reestablish a pleasant atmosphere. The young man turned out to be a classical ballet dancer from the Dutch National Ballet, with Surinamese origins, who had performed in Vienna. But the lady continued to be out of her wits with fear—xenophobia, in a literal sense. She could not get beyond the idea that when the dancer and Gert Jan talked music, they must mean African tam-tam. Luckily, the dancer was well traveled and did not take offense. The three arrived in Amsterdam safely after some polite chitchatting in English.

* Social scientists use the terms in-group and out-group. In-group refers to what we intuitively feel to be “we,” while out-group refers to “they.” Humans really function in this simple way: we have a persistent need to classify others in either group. The definition of in-group is quite variable in some societies, but it is always noticeable. We use it for family versus in-laws (“the cold side of the family”), for our team versus the opponents, for people looking like us versus another race.

* In we-versus-they experiments, physiological measurements can be used alongside questionnaires to measure fear. People’s bodies can tell stories that their minds feel as taboo. These results confirm that family in a very wide sense is linked to human social biology and that ethnic characteristics are important as a quick aid in determining who belongs. People are we-versus-they creatures. In infancy they can learn to consider anyone, or any kind of face, as “we,” but after a few months their recognition is fixed. Later in life it becomes hard for people to change intuitive we-they responses to racial characteristics. Physiological reactions to a we-they situation can be based on any distinction among groups—even that among students from different university departments.15

* A book by a Frenchman about his visit to the United States contains the following text: “The American ministers of the Gospel do not attempt to draw or to fix all the thoughts of man upon the life to come; they are willing to surrender a portion of his heart to the cares of the present. . . . If they take no part themselves in productive labor, they are at least interested in its progress, and they applaud its results.”

The author, we might think, refers to U.S. TV evangelists. In fact, he was a French visitor, Alexis de Tocqueville, and his book appeared in 1835.

* In a peaceful revolution—the last revolution in Swedish history—the nobles of Sweden in 1809 deposed King Gustav IV, whom they considered incompetent, and surprisingly invited Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, a French general who served under their enemy Napoleon, to become king of Sweden. Bernadotte accepted and became King Charles XIV

John; his descendants have occupied the Swedish throne to this day. When the new king was installed, he addressed the Swedish parliament in their language. His broken Swedish amused the Swedes, and they roared with laughter. The Frenchman who had become king was so upset that he never tried to speak Swedish again.

In this incident Bernadotte was a victim of culture shock: never in his French upbringing and military career had he experienced subordinates who laughed at the mistakes of their superior. Historians tell us he had more problems adapting to the egalitarian Swedish and Norwegian mentality (he later became king of Norway as well) and to his subordinates’ constitutional rights. He was a good learner, however (except for language), and he ruled the country as a highly respected constitutional monarch until 1844.

* Table 3.1 shows high power dis tance val ues for most Asian countries (such as Malaysia and the Philippines), for Eastern European countries (such as Slovakia and Russia), for Latin countries (Latin America, such as Panama and Mexico, and to a somewhat lesser extent Latin Europe, such as France and Wallonia, the French-speaking part of Belgium), for Arabicspeaking countries, and for Afric an count ries. The table shows low values for German-speaking countries, such as Austria, the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and Germany; for Israel; for the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania); for the United States; for Great Brit ain and the white parts of its form er empire (New Zealand, Ireland, Australia, Canada); and for the Netherlands (but not for Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, which scored quite similar to Wallonia). Sweden scored 31 and France 68. If such a difference existed already two hundred years ago—for which, as will be argued, there is a good case—this explains Bernadotte’s culture shock.

* The fact that less-educated, low-status employees in various Western countries hold more “authoritarian” values than their higher-status compatriots had already been described by sociologists. These authoritarian values not only are manifested at work but also are found in their home situations. A study in the United States and Italy in the 1960s showed that working-class parents demanded more obedience from their children than middle-class parents but that the difference was larger in the United States than in Italy.

* “The often strongly emotional character of hierarchical relationships in France is intriguing. There is an extreme diversity of feelings towards superiors: they may be either adored or despised with equal intensity. This situation is not at all universal: we found it neither in the Netherlands nor in the United States.25”

* In large-power-distance countries, people read relatively few newspapers (but they express confi dence in those they read), and they rarely discuss politics: political disagreements soon deteriorate into violence. The system often admits only one political party; where more parties are allowed, the same party usually always wins. The political spectrum, if it is allowed to be visible, is characterized by strong right and left wings with a weak center, a political refl ection of the polarization between dependence and counterdependence described earlier. Incomes in these countries are very unequally distributed, with a few very rich people and many very poor people. Moreover, taxation protects the wealthy, so that incomes after taxes can be even more unequal than before taxes. Labor unions tend to be government controlled; where they are not, they are ideologically based and involved in politics.

Authority in small-power-distance societies was qualified by Inglehart as secular-rational: being based on practical considerations rather than on tradition. In these societies the feeling dominates that politics and religion should be separated. The use of power should be subject to laws and to the judgment between good and evil. Inequality is considered basically undesirable; although unavoidable, it should be minimized by political means. The law should guarantee that everybody, regardless of status, has equal rights. Power, wealth, and status need not go together—it is even considered a good thing if they do not. Status symbols for powerful people are suspect, and leaders may enhance their informal status by renouncing formal symbols (for example, taking the streetcar to work). Most countries in this category are relatively wealthy, with a large middle class. The main sources of power are one’s formal position, one’s assumed expertise, and one’s ability to give rewards. Scandals usually mean the end of a political career. Revolutions are unpopular; the system is changed in evolutionary ways, without necessarily deposing those in power. Newspapers are read a lot, although confidence in them is not high. Political issues are often discussed, and violence in domestic politics is rare. Countries with smallpower-distance value systems usually have pluralist governments that can shift peacefully from one party or coalition to another on the basis of election results. The political spectrum in such countries shows a powerful center and weaker right and left wings. Incomes are less unequally distributed than in large-power-distance countries. Taxation serves to redistribute income, making incomes after taxes less unequal than before. Labor unions are independent and less oriented to ideology and politics than to pragmatic issues on behalf of their members.

* European countries in which the native language is Romance (French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish) scored medium to high on the power distance scale (in Table 3.1. from 50 for Italy to 90 for Romania). European countries in which the native language is Germanic (Danish, Dutch, English, German, Norwegian, Swedish) scored low (from 11 in Austria to 40 in Luxembourg). There seems to be a relationship between language area and present-day mental software regarding power distance. The fact that a country belongs to a language area is rooted in history: Romance languages all derive from Low Latin and were adopted in countries once part of the Roman Empire, or, in the case of Latin America, in countries colonized by Spain and Portugal, which themselves were former colonies of Rome. Germanic languages are spoken in countries that remained “barbaric” in Roman days, in areas once under Roman rule but reconquered by barbarians (such as England), and in former colonies of these entities. Thus, some roots of the mental program called power distance go back at least to Roman times—two thousand years ago. Countries with a Chinese (Confucian) cultural inheritance also cluster on the medium to high side of the power distance scale—and they carry a culture at least four thousand years old.

* The result is that a country’s PDI score can be fairly accurately predicted from the following:

■ The country’s geographic latitude (higher latitudes associated with lower PDI) ■ Its population size (larger size associated with higher PDI) ■ Its wealth (richer countries associated with lower PDI)34

Geographic latitude (the distance from the equator of a country’s capital city) alone allows us to predict 43 percent of the differences (the variance) in PDI values among the fifty countries in the original IBM set. Latitude and population size together predicted 51 percent of the variance; and latitude, population size, plus national wealth (per capita gross national income in 1970, the middle year of the survey period), predicted 58 percent.

* At lower latitudes (that is, more tropical climates), agricultural societies generally meet a more abundant nature. Survival and population growth in these climates demand a relatively limited intervention of humans with nature: everything grows. In this situation the major threat to a society is the competition of other human groups for the same territory and resources. The better chances for survival exist for the societies that have organized themselves hierarchically and in dependence on one central authority that keeps order and balance. At higher latitudes (that is, moderate and colder climates), nature is less abundant. There is more of a need for people’s intervention with nature in order to carve out an existence. These conditions support the creation of industry next to agriculture. Nature, rather than other humans, is the first enemy to be resisted. Societies in which people have learned to fend for themselves without being too dependent on more powerful others have a better chance of survival under these circumstances than societies that educate their children toward obedience.

* Van de Vliert studied the effect of climate on culture, opposing survival (high PDI) cultures to self-expression (low PDI) cultures. He proves that demanding cold or hot climates have led to survival cultures, except in affluent societies that have the means to cope with heat and cold, where we find self-expression cultures. In temperate climates, the role of affluence is less pronounced.36 National wealth in itself stands for a lot of other factors, each of which could be both an effect and a cause of smaller power distances. Here we are dealing with phenomena for which causality is almost always spiral, such as the causality of the chicken and the egg. Factors associated with more national wealth and less dependence on powerful others are as follows:

■ Less traditional agriculture ■ More modern technology ■ More urban living ■ More social mobility ■ A better educational system ■ A larger middle class

* Amedium-size Swedish high-technology corporation was approached with a profitable opportunity by a compatriot, a businessman with good contacts in Saudi Arabia. The corporation sent one of its engineers—let us call him Johannesson—to Riyadh, where he was introduced to a small Saudi engineering firm run by two brothers in their

mid-thirties, both with British university degrees. The request was to assist in a development project on behalf of the Saudi government.

However, after six visits over a period of two years, nothing seemed to happen. Johannesson’s meetings with the brothers were always held in the presence of the Swedish businessman who had established the first contact. This annoyed him and his superiors, because they were not at all sure that this businessman did not have contacts with their competitors as well—but the Saudis wanted the intermediary to be there. Discussions often dwelt on issues having little to do with the business—for instance, Shakespeare, of whom both brothers were fans. Just when Johannesson’s superiors started to seriously doubt the wisdom of the corporation’s investment in these expensive trips, a fax arrived from Riyadh inviting Johannesson for an urgent visit. A contract worth several million dollars was ready to be signed. Back he went. From one day to the next, the Saudis’ attitude had changed: the b usinessman-intermediary’s presence was no longer necessary, and Johannesson for the fi rst time saw the Saudis smile and even make jokes. So far, so good—but the story goes on. Acquiring the remarkable order contributed to Johannesson’s being promoted to a management position in a different division. Thus, he was no longer in charge of the Saudi account. A successor was nominated, another engineer with considerable international experience, whom Johannesson personally introduced to the Saudi brothers. A few weeks later another fax arrived from Riyadh; in this one the Saudis threatened to cancel the contract over a detail in the delivery conditions. Johannesson’s help was requested. When he arrived in Riyadh, it appeared that the confl ict was over a minor issue and could easily be resolved—but only, the Saudis felt, with Johannesson as the corporation’s representative. So, the corporation twisted its structure to allow Johannesson to handle the Saudi account even though his main responsibilities were now in a completely different field.

The Swedes and the Saudis in this true story have different concepts of the role of personal relationships in business. For the Swedes, business is done with a company; for the Saudis, it’s done with a person whom one has learned to know and trust. When one does not know another person well enough, it is best that contacts take place in the presence of an intermediary or go-between, someone who knows and is trusted by both parties. At the root of the difference between these cultures is a fundamental issue in human societies: the role of the individual versus the role of the group.

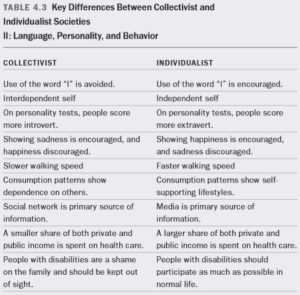

The vast majority of people in our world live in societies in which the interest of the group prevails over the interest of the individual. We will call these societies collectivist, using a word that to some readers may have political connotations, but the word is not meant here in any political sense. It does not refer to the power of the state over the individual; it refers to the power of the group. The first group in our lives is always the family into which we are born. Family structures, however, differ among societies. In most collectivist societies, the “family” within which the child grows up consists of a number of people living closely together: not just the parents and other children but also, for example, grandparents, uncles, aunts, servants, or other housemates. This is known in cultural anthropology as the extended family. When children grow up, they learn to think of themselves as part of a “we” group, a relationship that is not voluntary but is instead given by nature. The “we” group is distinct from other people in society who belong to “they” groups, of which there are many. The “we” group (or in-group) is the major source of one’s identity and the only secure protection one has against the hardships of life. Therefore, one owes lifelong loyalty to one’s in-group, and breaking this loyalty is one of the worst things a person can do. Between the person and the ingroup, a mutual dependence relationship develops that is both practical and psychological. A minority of people in our world live in societies in which the interests of the individual prevail over the interests of the group, societies that we will call individualist. In these, most children are born into families consisting of two parents and, possibly, other children; in some societies there is an increasing share of one-parent families. Other relatives live elsewhere and are rarely seen. This type is the nuclear family (from the Latin nucleus, meaning “core”). Children from such families, as they grow up, soon learn to think of themselves as “I.” This “I,” their personal identity, is distinct from other people’s “I”s, and these others are classified not according to their group membership but instead according to individual characteristics. Playmates, for example, are chosen on the basis of personal preferences. The purpose of education is to enable children to stand on their own feet. Children are expected to leave the parental home as soon as this has been achieved. Not infrequently, children, after having left home, reduce relationships with their parents to a minimum or break them off altogether. Neither practically nor psychologically is the healthy person in this type of society supposed to be dependent on a group.

* Exclusionism can be defined as the cultural tendency to treat people on the basis of their group affiliation and to reserve favors, services, privileges, and sacrifi ces for friends, relatives, and other groups with which one identifies, while excluding outsiders from the circle of those who deserve such privileged treatment. While exclusionist cultures strive to achieve harmony and good relationships within one’s in-group, they may be indifferent, inconsiderate, rude, and sometimes even hostile toward members of out-groups. Universalism is the opposite cultural tendency: treating people primarily on the basis of who they are as individuals and disregarding their group affiliations.

* Many countries that score high on the power distance index (Table 3.1) score low on the individualism index (Table 4.1), and vice versa. In other words, the two dimensions tend to be negatively correlated: large-power

distance countries are also likely to be more collectivist, and small-power distance countries to be more individualist.

* In the collectivist family, children learn to take their bearings from others when it comes to opinions. Personal opinions do not exist: opinions are predetermined by the group. If a new issue comes up on which there is no established group opinion, some kind of family conference is necessary before an opinion can be given. A child who repeatedly voices opinions deviating from what is collectively felt is considered to have a bad character. In the individualist family, on the contrary, children are expected and encouraged to develop opinions of their own, and a child who always only refl ects the opinions of others is considered to have a weak character. The behavior corresponding with a desirable character depends on the cultural environment. The loyalty to the group that is an essential element of the collectivist family also means that resources are shared. If one member of an extended family of twenty persons has a paid job and the others do not, the earning member is supposed to share his or her income in order to help feed the entire family. On the basis of this principle, a family may collectively cover the expenses for sending one member to get a higher education, expecting that when this member subsequently gets a well-paid job, the income will also be shared. In individualist cultures, parents will be proud if children at an early age take small jobs in order to earn pocket money of their own, which they alone can decide how to spend. In the Netherlands, as in many other individualist Western European countries, the government contributes substantially to the living expenses of students. In the 1980s the system was changed from an allowance to the parents to an allowance directly to the students themselves, which stressed their independence. Boys and girls are treated as independent economic actors from age eighteen onward. In the United States it is normal for students to pay for their own studies by getting temporary jobs and personal loans; without government support they, too, are less dependent on their parents and not at all on more distant relatives.

* U.S. anthropologist and popular author Edward T. Hall (1914–2009) distinguished cultures on the basis of their way of communicating along a dimension from high-context to low-context.27 A high-context communication is one in which little has to be said or written because most of the information is either in the physical environment or supposed to be known by the persons involved, while very little is in the coded, explicit part of the message. This type of communication is frequent in collectivist cultures; Hadjiwibowo’s family visit is a prime example. A low-context communication is one in which the mass of information is vested in the explicit code, which is typical for individualist cultures. Lots of things that in collectivist cultures are self-evident must be said explicitly in individualist cultures. American business contracts are much longer than Japanese business contracts.

* In summary, in the collectivist society, the personal relationship prevails over the task and should be established first, whereas in the individualist society, the task is supposed to prevail over any personal relationships.

* Alfred Kraemer, an American author in the fi eld of intercultural communication, cited the following comment in a Russian literary journal by a poet, Vladimir Korotich, who had completed a two-month lecture tour at American universities:

“Attempts to please an American audience are doomed in advance, because out of twenty listeners five may hold one point of view, seven another, and eight may have none at all.”

What strikes the Western reader about this comment is not the described attitudes of American students but the fact that Korotich expected otherwise. He was obviously accustomed to audiences in which people would not express a confronting view, a characteristic of a collectivist culture. Table 4.1 shows Russia to score considerably more collectivist than Western countries.

* Individualist countries tend to be wealthier and to have smaller power distances than collectivist ones.

* The right to privacy is a central theme in many individualist societies that does not fi nd the same sympathy in collectivist societies, where it is seen as normal and right that one’s in-group can at any time invade one’s private life. The difference between a universalist and a particularist treatment of customers, illustrated by the Johannesson case, applies to the functioning of the state as a whole. In the individualist society, laws and rights are supposed to be the same for all members and to be applied indiscriminately to everybody (whether this standard is always met is another question). In the collectivist society, laws and rights may differ from one category of people to another—if not in theory, then in the way laws are administered—and this is not seen as wrong.

* Individualist societies not only practice individualism but also consider it superior to other forms of mental software. Most Americans feel that individualism is good and that it is at the root of their country’s greatness. On the other hand, the late chairman Mao Zedong of China identified individualism as evil. He found individualism and liberalism responsible for selfishness and aversion to discipline; they led people to placing personal interests above those of the group or simply to devoting too much attention to their own things. In Table 4.1 the places with a predominantly Chinese population all score very low on IDV (Hong Kong 25, mainland China 20, Singapore 20, Taiwan 17).

* The choice between individualism and collectivism at the society level has considerable implications for economic theories. Economics as a discipline was founded in Britain in the eighteenth century; among the founding fathers, Adam Smith (1723–90) stands out. Smith assumed that the pursuit of self-interest by individuals through an “invisible hand” would increase the wealth of nations. This is an individualist idea from a country that even today ranks high on individualism. Economics has remained an individualist science, and most of its leading contributors have come from strongly individualist nations such as Britain and the United States. However, because of the individualist assumptions on which economic theories are based, these theories as developed in the West are unlikely to apply in societies in which group interests prevail. This point has profound consequences for development assistance to poor countries and for economic globalization. There is a dire need for alternative economic theories that take into account cultural differences on this dimension.

* We found that a country’s IDV score can be fairly accurately predicted from two factors:

■ The country’s wealth (richer countries associated with higher IDV) ■ Its geographical latitude (countries closer to the equator associated with lower IDV)

* Wealth (GNI per capita at the time of the IBM surveys) explained no less than 71 percent of the differences in IDV scores for the original fi fty IBM countries.

* When a country’s wealth increases, its citizens get access to resources that allow them to do their own thing. The storyteller in the village market is replaced by TV sets, first one per village, but soon more. In wealthy Western family homes, every family member may have his or her own TV set. The caravan through the desert is replaced by a number of buses, and these by a larger number of automobiles, until each adult family member drives a different car. The village hut in which the entire family lives and sleeps together is replaced by a house with a number of private rooms. Collective life is replaced by individual life.

* Besides national wealth, the only other measure statistically related to IDV was geographic latitude: the distance from the equator of a country’s capital city. It explained an additional 7 percent of the IDV differences. In Chapter 3 latitude was the fi rst predictor of power distance scores. As we argued there, in countries with moderate and cold climates, people’s survival depends more on their ability to fend for themselves. This circumstance favors educating children toward independence from more powerful others (lower PDI). It also seems to favor a degree of individualism.

* On the other hand, in parts of Western Europe, in particular in England, Scotland, and the Netherlands, individualist values could be recognized centuries ago, when the average citizen in these countries was still quite poor and the economies were overwhelmingly rural. India is another example of a country with a rather individualistic culture despite poverty.

* As a young Dutch engineer, Geert once applied for a junior management job with an American engineering company that had recently settled in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. He felt well qualified, with a degree from the leading technical university of the country, good grades, a record of active participation in student

associations, and three years’ experience as an engineer with a well known (although somewhat sleepy) Dutch company. He had written a short letter to the company indicating his interest and providing some salient personal data. He was invited for an interview, and after a long train ride he sat facing the American plant manager. Geert behaved politely and modestly, as he knew an applicant should, and waited for the other man to ask the usual questions that would enable him to find out how qualified Geert was. To his surprise, the plant manager touched on very few of the areas that Geert thought should be discussed. Instead, he asked about some highly detailed facts pertaining to Geert’s experience in tool design, using English words that Geert did not know, and the relevance of the questioning escaped him. Those were things he could learn within a week once he worked there. After half an hour of painful misunderstandings, the interviewer said, “Sorry—we need a fi rst-class man.” And Geert was out on the street.

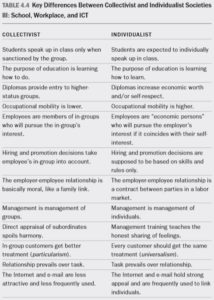

Assertiveness Versus Modesty

Years later Geert was the interviewer, and he met with both Dutch and American applicants. Then he understood what had gone wrong in that earlier case. American applicants, to Dutch eyes, oversell themselves. Their curricula vitae are worded in superlatives, mentioning every degree, grade, award, and membership to demonstrate their outstanding qualities. During the interview they try to behave assertively, promising things they are very unlikely to realize—such as learning the local language in a few months. Dutch applicants, in American eyes, undersell themselves. They write modest and usually short CVs, counting on the interviewer to fi nd out how good they really are by asking. They expect an interest in their social and extracurricular activities during their studies. They are careful not to be seen as braggarts and not to make promises they are not absolutely sure they can fulfi ll. American interviewers know how to interpret American CVs and interviews, and they tend to discount the information provided. Dutch interviewers, accustomed to Dutch applicants, tend to upgrade the information. The scenario for cross-cultural misunderstanding is clear. To an uninitiated American inter viewer, an uninitiated Dutch applicant comes across as a sucker. To an uninitiated Dutch interviewer, an uninitiated American applicant comes across as a braggart.

Dutch and American societies are reasonably similar on the dimensions of power distance and individualism as described in the two previous chapters, but they differ considerably on a third dimension, which opposes, among other things, the desirability of assertive behavior against the desirability of modest behavior. We will label it masculinity versus femininity.

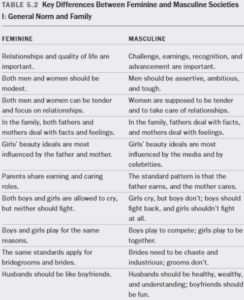

* A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

* In a feedback session in Denmark, Geert asked respondents why nobody in their company had considered “a married man having sexual relationships with a subordinate” as a valid reason for the man’s dismissal. A woman stood up and said, “Either she likes it, and then there is no problem, or she doesn’t like it, and then she will tell him to go to hell.” There are two pertinent assumptions in this answer: (most) Danish subordinates will not hesitate to speak up to their bosses (small power distance), and (most) male Danish bosses will “go to hell” if told so by a female subordinate (femininity).

In a study of “sexual harassment” in four countries in the 1990s, Brazilian students of both sexes differed from their colleagues in Australia, the United States, and Germany. They saw sexual harassment less as an abuse of power, less as related to gender discrimination, and more as a relatively harmless pastime.27 Brazil in the IBM research scored lower on MAS than the three other countries (49, versus 61, 62, and 66, respectively). Attitudes toward homosexuality are also affected by the degree of masculinity in the culture. In a comparison among Australia, Finland, Ireland, and Sweden, it was found that young homosexuals had more problems accepting their sexual orientation in Ireland and Australia, less in Finland, and least in Sweden. This is the order of the countries on MAS. Homosexuality tends to be felt as a threat to masculine norms and rejected in masculine cultures; this attitude is accompanied by an overestimation of its frequency. In feminine cultures, homosexuality is more often considered a fact of life.28

* Failing in school is a disaster in a masculine culture. In strongly masculine countries such as Japan and Germany, the newspapers carry reports each year about students who killed themselves after failing an examination. In a 1973 insider story, a Harvard Business School graduate reported four suicides—one teacher, three students—during his time at this elite American institution.33 Failure in school in a feminine culture is a relatively minor incident. When young people in these cultures take their lives, it tends to be for reasons unrelated to performance. Competitive sports play an important role in the curriculum in countries such as Britain and the United States. To a prominent U.S. sports coach the dictum is attributed, “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing,”34 which doesn’t encourage friendly encounters in sports. In most other European countries, sports are extracurricular and not a part of the school’s main activities.

* Historically, management is an Anglo-Saxon concept, developed in masculine British and American cultures. The English—and international—word management comes from the Latin manus, or “hand”; the modern Italian word maneggiare means “handling.” In French, however, the Latin root is used in two derivations: manège (a place where horses are drilled) and ménage (household); the former is the masculine side of management, the latter the feminine side. Classic American studies of leadership distinguished two dimensions: initiating structure versus consideration, or concern for work versus concern for people.48 Both are equally necessary for the success of an enterprise, but the optimal balance between the two differs for masculine and feminine cultures. A Dutchman who had worked with a prestigious consulting fi rm in the United States for several years joined the top management team of a manufacturing company in the Netherlands. After a few months he commented on the different function of meetings in his present job compared with his previous one. In the Dutch situation, meetings were occasions when problems were discussed and common solutions were sought; they served for making consensus decisions.49 In the U.S. situation as he had known it, meetings were opportunities for participants to assert themselves, to show how good they were. Decisions were made by individuals elsewhere. The masculinity-femininity dimension affects ways of handling industrial conflicts. In the United States as well as in other masculine cultures such as Britain and Ireland, there is a feeling that conflicts should be resolved by a good fight: “Let the best man win.” The industrial relations scene in these countries is marked by such fights.

* In feminine cultures such as the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, there is a preference for resolving conflicts by compromise and negotiation.

* Masculine culture countries strive for a performance society; feminine countries for a welfare society.

* Masculine countries tend to (try to) resolve international conflicts by fighting; feminine countries by compromise and negotiation (as in the case of work organizations). A striking example is the difference between the handling of the Åland crisis and of the Falkland crisis. The Åland islands are a small archipelago halfway be tween Sweden and Finland; as part of Finland they belonged to the tsarist Russian Empire. When Finland declared itself independent from Russia in 1917, the thirty thousand inhabitants of the islands in majority wanted to join Sweden, which had ruled them before 1809. The Finns then arrested the leaders of the pro-Swedish movement. After emotional negotiations in which the newly created League of Nations participated, all parties in 1921 agreed with a solution in which the islands remained Finnish but with a large amount of regional autonomy. The Falkland Islands are also a small archipelago disputed by two nations: Great Britain, which has occupied the islands since 1833, and nearby Argentina, which has claimed rights on them since 1767 and tried to get the United Nations to support its claim. The Falklands are about eight times as large as the Ålands but with less than one-fifteenth of the Ålands’ population: about 1,800 poor sheep farmers. The Argentinean military occupied the islands in April 1982, whereupon the British sent an expeditionary force that chased the occupants, at the cost of (officially) 725 Argentinean and 225 British lives and enormous financial expense. The economy of the islands, dependent on trade relations with Argentina, was severely jeopardized. What explains the difference in approach and in results between these two remarkably similar international disputes? Finland and Sweden are both feminine cultures; Argentina and Great Britain are both masculine. The masculine symbolism in the Falkland crisis was evident in the language used on either side. Unfortunately, the sacrifices resolved very little. The Falklands remain a disputed territory needing constant British subsidies and military presence; the Ålands have become a prosperous part of Finland, attracting many Swedish tourists.

* Masculine cultures worship a tough God or gods who justify tough behavior toward fellow humans; feminine cultures worship a tender God or gods who demand caring behavior toward fellow humans. Christianity has always maintained a struggle between tough, masculine elements and tender, feminine elements. In the Christian Bible as a whole, the Old Testament refl ects tougher values (an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth), while the New Testament refl ects more tender values (turn the other cheek). God in the Old Testament is majestic. Jesus in the New Testament helps the weak and suffers. Catholicism has produced some very masculine, tough currents (Templars, Jesuits) but also some feminine, tender ones (Franciscans); outside Catholicism we also fi nd groups with strongly masculine values (such as the Mormons) and groups with very feminine values (such as the Quakers and the Salvation Army). On average, countries with a Catholic tradition tend to maintain more masculine values and those with Protestant traditions more feminine values.74 Outside the Christian world there are also tough and tender religions. Buddhism in masculine Japan is very different from Buddhism in feminine Thailand. Some young men in Japan follow Zen Buddhist training aimed at self-development by meditation under a tough master. In the 1970s more than half of all young men in Thailand spent some time as a Buddhist monk, serving and begging.75 In Islam, Sunni is a more masculine version of the faith than Shia, which stresses the importance of suffering. In the IBM studies, Iran, which is predominantly Shiite, scored more feminine than the predominantly Sunnite Arabic-speaking countries.

* the best available predictor of a country’s degree of secularization was the degree of femininity of its culture—this in spite of the fact that women tend to be more religious than men. In masculine Christian countries, people rated their religiosity higher and attached more importance in their lives to God, Christian rites, orthodoxy, and Christian worldviews. Countries with feminine values had secularized faster than those with masculine ones; this applied across the board, including in the United States.

* Latin American countries varied considerably on the masculinity femininity scale. Small Central American countries as well as Peru and Chile scored feminine; Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador strongly masculine. One speculative explanation is that these differences reflect the inheritance of the different Indian civilizations dominant prior to the Spanish conquest. Most of Mexico inherited the tough Aztec culture, but the southern Mexican peninsula of Yucatan and the adjacent Central American republics inherited the less militant Maya culture. Peru and Northern Chile inherited the Inca culture, resembling the Maya.

* In the 1960s Arndt Sorge did his military service in the West German army. Near his hometown, where he spent his free weekends, there were barracks of the British “Army on the Rhine.” Sorge was keen on watching British motion pictures with the original sound track, which were shown in the British barracks, and he walked up to the sentry to ask whether he, as a German soldier, could attend. The sentry referred him to the sergeant of the guard, who called the second in command on the telephone and then tore a page out of a notebook, on which he wrote, “Mr Arndt Sorge has permission to attend film shows,” and signed it, adding that permission was granted by the second in command.

Sorge used his privilege not only on that occasion but also several other times, and the notebook page always opened the gate for him, in conjunction with his German army identity card. After he was demobilized, he asked the British sentry whether he, now as a civilian, could continue to come. The sentry looked at the notebook page, said, “This is for you personally,” and let him in. Arndt Sorge became an organization sociologist, and he remembers this experience as an example of how differently the British seemed to handle such an unplanned request in comparison with what he was accustomed to in the German army. The Germans would have taken more time and would have needed the permission of more authorities; they would have asked for more information about the applicant and issued a more formal document. Finally, the document would have been issued to him as a member of the armed forces, and there would have been no possibility of his using it after his demobilization.

Germany and Britain have a lot in common. Both are Western European countries, both speak a Germanic language, their populations are of roughly equal size, and the British royal family is of German descent. Yet it does not take a very experienced traveler to notice the considerable cultural difference between the two countries. Peter Lawrence is a British sociologist who wrote about Germany:

“What strikes a foreigner traveling in Germany is the importance attached to the idea of punctuality, whether or not the standard is realized. Punctuality, not the weather, is the standard topic of conversation for strangers in railway compartments. Long distance trains in Germany have a pamphlet laid out in each compartment called a Zugbegleiter (literally, “train accompanier”) which lists all the stops with arrival and departure times and all the possible connections en route. It is almost a national sport in Germany, as a train pulls into a station, for hands to reach out for the Zugbegleiter so that the train’s progress may be checked against the digital watch. When trains are late and it happens, the loudspeaker announcements relay this fact in a tone which falls between the stoic and the tragic. The worst category of lateness which fi gures in these announcements is unbestimmte Verspätung (indeterminable lateness: we don’t know how late it is going to be!) and this is pronounced as a funeral oration.”

Sorge’s surprise at the easygoing approach of the British sentry and Lawrence’s at the punctual German travelers suggest that the two countries differ in their tolerance of the ambiguous and the unpredictable. In the IBM research, Britain and Germany score exactly alike on the two dimensions of power distance (both 35) and masculinity (both 66). On individualism, though, the British score considerably higher (89 versus 67). The largest difference between the two countries, however, is on a fourth dimension, labeled uncertainty avoidance.

* Anxious cultures tend to be expressive cultures. They are the places where people talk with their hands and where it is socially acceptable to raise one’s voice, to show one’s emotions, and to pound the table. Japan may seem to be an exception in this respect; as with other Asians, the Japanese generally behave unemotionally in Western eyes. In Japan, however, and to some extent also in Korea and Taiwan, there is the outlet of getting drunk among colleagues after working hours. During these parties men release their pent-up aggression, even toward superiors, but the next day business continues as usual. Such drinking bouts represent one of the major institutionalized places and times for anxiety release.

* An American grandparent couple spent two weeks in a small Italian town babysitting for their grandchildren, whose American parents, temporarily located in Italy, were away on a trip. The children loved to play in the public piazza, amid lots of Italian children with their mothers or nannies. The American children were allowed to run around; they would fall down but get up again, and the grandparents felt there was little real danger. The Italians reacted quite differently. They would not let their children out of their sight for a moment, and when one fell down, an adult would immediately pick the child up, brush off the dirt, and console the child.14

* The strong uncertainty-a voidance sentiment can be summarized by the credo of xenophobia: “What is different is dangerous.” The weak uncertainty avoidance sentiment, on the contrary, is: “What is different is curious.”

Family life in high-UAI societies is inherently more stressful than where UAI is low. Feelings are more intense, and both parents and children express their positive sentiments as well as their negative sentiments more emotionally.

* Countries with weak uncertainty avoidance can show the opposite, an emotional horror of formal rules. People think that rules should be established only in case of absolute necessity, such as to determine whether traffi c should keep left or right. They believe that many problems can be solved without formal rules. Germans, coming from a fairly uncertainty avoiding culture, are impressed by the public discipline shown by the British in forming neat queues at bus stops and in shops. There is no law in Britain governing queuing behavior; it is based on a public habit continuously reinforced by social control. The paradox here is that although rules in countries with weak uncertainty avoidance are less sacred, they are often better followed. British queuing behavior is facilitated by the unemotional and patient nature of most British subjects. As argued earlier in this chapter, weak uncertainty avoidance also stands for low anxiety. At the workplace the anxiety component of uncertainty avoidance leads to noticeable differences between strong and weak uncertainty- avoidance societies. In strong uncertainty- avoidance societies, people like to work hard or at least to be always busy. Life is hurried, and time is money. In weak uncertainty avoidance societies, people are able to work hard if there is a need for it, but they are not driven by an inner urge toward constant activity. They like to relax. Time is a framework in which to orient oneself but not something one is constantly watching.

* In countries with strong uncertainty avoidance, there tend to be more— and more precise—laws than in those with weak uncertainty avoidance. Germany, for example, has laws for the event that all other laws become unenforceable (Notstandsgesetze), while Britain does not even have a written constitution. Labor-management relations in Germany have been codified in detail, while attempts to pass an Industrial Relations Act in Britain have never succeeded. In countries with weak uncertainty avoidance, a feeling prevails that if laws do not work, they should be withdrawn or changed. In countries with strong uncertainty avoidance, laws can fulfill a need for security even if they are not followed—very similar to religious commandments.

* In 1983 a sixteen-year-old high school student from Rotterdam, whom we will call Anneke, participated in a youth exchange program between Holland and Austria. She stayed with the family of a high school teacher in a middle-sized Austrian town. There were Dr. Riedl and his wife; their daughter, Hilde (of Anneke’s age); and two younger boys. Anneke went to school with Hilde. Her German improved rapidly. On Sundays she went to Mass with the Riedls, who were pious Roman Catholics. Anneke was a Protestant, but she did not mind; she liked the experience and the singing. She had taken her violin along to Austria, and after school she played pieces for violin and piano with Hilde. One day when Anneke had been with the Riedls for about two months, the dinner conversation somehow turned to the subject of Jewish people. The Riedls seemed to be tremendously prejudiced on the subject. Anneke became upset. She asked Mrs. Riedl whether she knew any Jewish people. “Of course not!” was the answer. Anneke felt the blood go to her face. “Well, you know one now,” she said. “I am Jewish. At least, my mother is from a Jewish family, and according to Jewish tradition anybody born from a Jewish mother is also Jewish.” The dinner ended in silence. The next morning Dr. Riedl took Anneke aside and told her that she could no longer eat with the Riedls. They would serve her separately. Nor could she go to church with them. They should have been told that she was a Jew. Anneke returned to Holland a few days later.63 Among European Union members, Austria and other central European countries in the IBM studies and their replications scored relatively high on uncertainty avoidance. In this part of Europe, ethnic prejudice, including anti-Semitism, has been rampant for centuries.

* The Riedl parents in our story were programmed with the feeling that what is different is dangerous, and they transferred this feeling to their children. We don’t know how the Riedl children experienced the incident or whether they became as prejudiced as their parents. Feelings of danger may be directed toward minorities (or even minorities from the past), toward immigrants and refugees, and toward citizens of other countries. Data from a European Commission report entitled Racism and Xenophobia in Europe (1997) showed that the opinion that immigrants should be sent back was strongly correlated with uncertainty avoidance.

* Strong uncertainty avoidance leading to intolerance of deviants and minorities has at times been costly to countries. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal by the Catholic kings after the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors (1492) has deprived these countries of some of their most enterprising citizens and is believed to have contributed to the decadence of the empire in the following centuries.

* religious conversion does not cause a total change in cultural values. The value complexes described by the dimensions of power distance, individualism or collectivism, masculinity or femininity, and uncertainty avoidance seem to have survived religious conversions.

* Across all countries with a Christian majority, there is a strong correlation between the percentage of Catholics in the population (as opposed to Protestants) and the country’s UAI. A second correlation is with masculinity, implying that where Catholicism prevails, masculine values tend to prevail as well—for instance, in refusing to admit women to leadership positions (see Chapter 5).66 The correlation with uncertainty avoidance is easy to interpret, as the Catholic Church supplies its believers with a certainty that most protestant groups lack (apart from some of the smaller sects). The Catholic Church appeals to cultures with a need for such certainty. Within the Protestant nations the dominant cultures have equipped people with a lesser need for certainty. Those who do need it fi nd a spiritual home in sects and fundamentalist groups. Both within Islam and within Judaism there is also a clearly visible confl ict between more and less uncertainty-avoiding factions, the fi rst dogmatic, intolerant, fanatical, and fundamentalist (“There is only one Truth and we have it”), the second pragmatic, tolerant, liberal, and open to the modern world.

* In strong uncertainty- avoidance cultures, we find intolerant political ideologies; in weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures, we find tolerant ones. The respect for what are commonly called human rights assumes a tolerance for people with different political ideas. Violation of human rights in some countries is rooted in the strong uncertainty avoidance within their cultures. In other countries it is rather an outcome of a power struggle (and related to power distance) or of collectivist intergroup strife. In the area of philosophy and science,68 grand theories are more likely to be conceived within strong uncertainty- avoidance cultures than in weak uncertainty avoidance ones. The quest for Truth is an essential motivator for a philosopher. In Europe, Germany and France have produced more great philosophers than Britain and Sweden (for example, Descartes, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, and Sartre). Weak uncertainty- avoidance cultures have produced great empiricists, people developing conclusions from observation and experiments rather than from pure reflection (such as Newton, Linnaeus, and Darwin). In serving as peer reviewers of manuscripts submitted to scientific journals, we notice that papers by Germans and French writers often present broad conclusions unsupported by data. Manuscripts by British and American writers present extensive data analysis but shy away from bold conclusions. The Germans and French tend to reason by deduction, British and Americans by induction.69 Scientific disputes sometimes hide cultural assumptions. A famous example is the discussion between the German physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and his Danish colleague Niels Bohr (1885–1962) on whether certain processes inside the atom are governed by laws or random. “I cannot imagine God playing dice,” Einstein is supposed to have said. Bohr could; recent research has proved him right, not Einstein. Denmark scores very low on uncertainty avoidance (rank 74, score 23). A society’s level of uncertainty avoidance has practical consequences regarding the ability of people who hold different convictions to be personal friends. Stories of scientists who separated their ties of friendship after a scientific disagreement tend to come from high-UAI countries. The conflict between psychiatrists Sigmund Freud (Austria) and Carl Gustav Jung (Switzerland) is one example. In weak uncertainty-avoidance countries, different scientific opinions do not necessarily bar friendships.

On uncertainty avoidance we again find the countries with a Romance language together. These heirs of the Roman Empire all score on the strong uncertainty-avoidance side. The Chinese-speaking countries Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore score low on uncertainty avoidance, as do countries with important minorities of Chinese origin: Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia. The Roman and Chinese Empires were both powerful centralized states, supporting a culture pattern in their populations prepared to take orders from the center. The two empires differed, however, in an important respect. The Roman Empire had developed a unique system of codified laws that in principle applied to all people with citizen status regardless of origin. The Chinese Empire never knew this concept of law.

* The fifth dimension was defined as follows: long-term orientation stands for the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards—in particular, perseverance and thrift. Its opposite pole, short-term orientation, stands for the fostering of virtues related to the past and present—in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of “face,” and fulfilling social obligations. Table 7.1 lists index scores on the new dimension for the twenty-three countries that participated in the CVS. The top positions are occupied by China and other East Asian countries. (Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore were known in the last decades of the twentieth century as the “Five Dragons” because of their fast economic growth.) Continental European countries occupied a middle range. Great Britain and its Anglo partners Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada scored on the short-term side. The African countries Zimbabwe and Nigeria scored very short-term, as did the Philippines and Pakistan.

* Marriage in high-LTO countries is a pragmatic, goal-oriented arrangement. Questions in the 1990–93 WVS about “things that make a marriage successful” showed that for families in high-LTO countries, living with in-laws was considered normal, and differences in tastes and interests between spouses did not matter.

* In summary, family life in the high-LTO culture is a pragmatic arrangement but is supposed to be based on real affection and with attention paid to small children. The children learn thrift, not to expect immediate gratification of their desires, tenacity in the pursuit of their goals, and humility. Self-assertion is not encouraged.14 Children growing up in a low-LTO culture experience two sets of norms. One is toward respecting “musts”: traditions, face-saving, being seen as a stable individual, respecting the social codes of marriage even if love has gone, and reciprocation of greetings, favors, and gifts as a social ritual. The other is toward immediate need gratification, spending, and sensitivity to social trends in consumption (“keeping up with the Joneses”). There is a potential tension between these two sets of norms that leads to a wide variety of individual behaviors.

* Dr. Rajendra Pradhan was a Nepalese anthropologist who in 1987–88 conducted a ten-month fi eld research project in the Dutch village of Schoonrewoerd. He thus reversed the familiar pattern of Western anthropologists doing fi eld research in Eastern villages. Schoonrewoerd was a typical Dutch village in the rural heart of the province of South Holland, with 1,500 inhabitants and two churches from different Calvinist Protestant denominations. Dr. Pradhan became a regular churchgoer in both, and he established his contacts with the local population predominantly through the congregations. He was often invited to people’s homes for coffee after church, and the topic, usually, was religion. He used to explain that his parents respected Hindu rituals but that he stopped doing this, because it would take him too much time. His Dutch hosts always wanted to know what he believed—an exotic question to which he did not have a direct answer. “Everybody over here talks about believing, believing, believing,” he said, bewildered. “Where I come from, what counts is the ritual, in which only the priest and the head of the family participate. The others watch and make their offerings. Over here so much is mandatory. Hindus will never ask, ‘Do you believe in God?’ Of course one should believe, but the important thing is what one does.”

* Uncertainty-avoiding cultures foster a belief in an absolute Truth, and uncertainty-accepting cultures take a more relativistic stance. In Western thinking this is an important choice, refl ected in key values. In Eastern thinking the question of Truth is less relevant. Long- versus short-term orientation can be interpreted as dealing with a society’s search for Virtue.

* Eastern religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Shintoism, and Taoism) are separated from Western religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) by a deep philosophical dividing line. The three Western religions belong to the same thought family; historically, they grew from the same roots. As argued in Chapter 6, all three are based on the existence of a Truth that is accessible to the true believers. All three have a Book. In the East neither Confucianism, which is a nonreligious ethic, nor any major religion is based on the assumption that there is a Truth that a human community can embrace. They offer various ways in which a person can improve him- or herself; however, these consist not of believing, but of ritual, meditation, or ways of living. Some of these may lead to a higher spiritual state and, eventually, to unification with God or gods. This difference in thinking explains why Dr. Pradhan was so puzzled by the question about what he believed. It is an irrelevant question in the East. What one does is important. U.S. mythologist Joseph Campbell, comparing Western and Eastern religious myths, concluded that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam separate matter and spirit, while Eastern religions and philosophers have kept them integrated.28 This difference in thinking also explains why a questionnaire invented by Western minds produced a fourth dimension dealing with Truth; a questionnaire invented by Eastern minds found a fourth dimension dealing with Virtue.

The Western concern with Truth is supported by an axiom in Western logic that a statement excludes its opposite: if A is true, B (which is the opposite of A) must be false. Eastern logic does not have such an axiom. If A is true, its opposite B may also be true, and together they produce a wisdom superior to either A or B. Human truth in this philosophical approach is always partial. People in East and Southeast Asian countries see no problem in adopting elements from different religions or adhering to more than one religion at the same time. In countries with such a philosophical background, a practical nonreligious ethical system like Confucianism can become a cornerstone of society. In the West ethical rules tend to be derived from religion: Virtue from Truth. According to Danish sinologist Verner Worm, the Chinese give priority to common sense over rationality. Rationality is abstract, analytical, and idealistic, with a tendency to logical extremes, whereas the spirit of common sense is more human and in closer contact with reality.30 Western psychology assumes that people seek cognitive consistency, meaning that they avoid mutually conflicting bits of information. This seems to be less the case in East and Southeast Asian countries.31 In comparison with North Americans, the Chinese viewed disagreement as less harmful to personal relationships than injury or disappointment. A different opinion did not hurt their egos.32

* Korean psychologist Uichol Kim believes the Western way of practicing psychology does not fit in East Asia:

“Psychology . . . is deeply enmeshed with Euro-American cultural values that champion rational, liberal and individualistic ideals. . . . This belief affects how conferences are organized, research collaborations are developed, research is funded, and publications are accepted. In East Asia, human relationships that can be characterized as being “virtue-based” rather than “rights-based” occupy the center stage. Individuals are considered to be linked in a web of inter-relatedness and ideas are exchanged through established social networks.”

* During the Industrial Revolution in the West, the search for Truth led to the discovery of laws of nature that could then be exploited for the sake of human progress. Chinese scholars, despite their high level of civilization, never discovered Newton’s laws. They were simply not looking for laws. The Chinese script betrays this lack of interest in generalizing. It needs three thousand or more different characters, one for each syllable, while by splitting the syllables into separate letters, Western languages need only about thirty signs. Western analytical thinking focused on elements, while Eastern synthetic thinking focused on wholes. A Japanese Nobel Prize winner in physics is quoted as having said that “the Japanese mentality is unfi t for abstract thinking.”34

* From 1970 to 2000 some countries were extremely successful in moving from “rags to riches.” The absolute winners were the fi ve Dragons: Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan—this in spite of a serious economic crisis in their region in 1997. In U.S. dollars, Taiwan’s 2000 GNI per capita was thirty-six times as high as its 1970 GNI per capita. Japan’s nominal GNI per capita increased by a factor of eighteen. On the other hand, the GNIs per capita of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America rose insignificantly or not at all. The economic success of the Dragons had not been predicted by economists. (Even after it happened, some failed for a time to recognize it.) A forecast for the region by prominent World Bank economists in the American Economic Review in 196664 did not even include Hong Kong and Singapore, because they were considered insignificant; it underrated the performances of Taiwan and South Korea and overrated those of India and Sri Lanka. Fifteen years later Singapore, with a population of 2.5 million, exported more than India with its 700 million. After the Dragons’ economic miracle had become undeniable, economics had no explanation for it. According to economic criteria, Colombia, for example, should have outperformed South Korea, while the reverse was true.65

* The development of East Asia was strongly guided by a desire to learn from others. Japan has actively studied European (in particular, Dutch) science and technology since the seventeenth century. Western fads and fashions are popular in East Asia even where governments don’t like them. Likewise, Eastern European countries in spite of communism have always taken the West as a model. This desire to learn from others is not necessarily present in countries scoring low on the LTO-WVS index.

* In its special Christmas edition, at a time when people in the traditionally Christian world are supposed to be merry and happy, the well-known British magazine The Economist once published the following story: “Once a week, on Sundays, Hong Kong becomes a different city. Thousands of Filipina women throng into the central business district, around Statue Square, to picnic, dance, sing, gossip, and laugh. . . . They hug. They chatter. They smile. Humanity could stage no greater display of happiness. This stands in stark contrast to the other six days of the week. Then it is the Chinese, famously cranky and often rude, and expatriate businessmen, permanently stressed, who control the center. On these days, the Filipinas are mostly holed up in the 154,000 households across the territory where they work as “domestic helpers” or amahs in Cantonese. There they suffer not only the loneliness of separation from their own families, but often virtual slavery under their Chinese or expatriate masters. Hence a mystery: those who should be Hong Kong’s most miserable are, by all appearances, its happiest.”

* Indulgence stands for a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun. Its opposite pole, restraint, reflects a conviction that such gratifi cation needs to be curbed and regulated by strict social norms.

* The indulgence versus restraint dimension solves the paradox of the poor Filipinas who are happier than the rich citizens of Hong Kong. The Philippines in Table 8.1 can be seen to rank higher on indulgence than Hong Kong, but still a lot lower than societies in northern Latin America or some western African nations.

* U.S. psychologist David Schmitt founded the International Sexuality Description Project and coordinated a number of interesting cross kcultural studies under its umbrella. One of them focused on what he called sociosexuality. According to Schmitt, this is a single strategic dimension of human mating:39

“Those who are relatively low on this dimension are said to possess a restricted sociosexual orientation—they tend toward monogamy, prolonged courtship, and heavy emotional investment in long-term relationships. Those residing at the high end of sociosexuality are considered more unrestricted in mating orientation, they tend toward promiscuity, are quick to have sex, and experience lower levels of romantic relationship closeness.”

The findings of Schmitt and his team show that self-reported female sociosexuality is strongly positively correlated with individualism/universalism (and strongly negatively with collectivism/exclusionism). This could mean that women in Western countries are more liberated sexually, but a parallel interpretation, which does not preclude the first one, is that women in collectivist countries are more inhibited when discussing their sexuality. It is interesting that the reported male sociosexuality differences do not correlate significantly with individualism and exclusionism. Men, all over the world, are probably less reluctant to talk about sex, and in many cultures they are actually inclined to boast about their exploits—be they real or imaginary.

* Russian management professor and cross-cultural expert Sergey Myasoedov is known across Eastern European business schools for his colorful narratives that illustrate cultural confl icts between American expatriate managers and local employees or customers. He noticed that American front-desk personnel are required to smile at the customers. This practice seems normal in a generally indulgent and happy culture such as that of the United States. But when a company—in the present case, McDonald’s— tries to mimic its American practices in a highly restrained society, there may be unexpected consequences:

“When they came to Russia, they brought their very strong corporate culture. They decided to train the Russian sales boys and girls. They wanted to get them to smile in the McDonald’s way that makes one display all thirty-two teeth. Yet, sometime later, the McDonald’s experts found out that Russian customers were shocked by those broad smiles. They stared in amazement at the sales personnel: “Why are you grinning at me?” They did their research and found that a broad smile at a stranger does not work in Russia. The Russians never smile like that when they run across a stranger. When somebody does that to a Russian, the likely reaction is “What is wrong with this person?” 42

These differences also translate into norms for the public image of political leaders. In the United States, maintaining a poker face would be a virtual death sentence for a political candidate or a holder of a highranking political office. American public figures are expected to exude joy and optimism even if they are privately worried about the way their political careers are going. Over in Russia, a stern face is a sign of seriousness, and it only seems to bolster the high rating that Vladimir Putin has always enjoyed. Geert postulates that indulgence also explains the norm of smiling in photographs (“say cheese”). His Eastern European friends lack this habit.43