Grok says: The concepts of buffered identity and porous identity stem from philosophical and cultural discussions, particularly associated with Charles Taylor’s work in A Secular Age. They describe contrasting ways in which individuals experience their sense of self in relation to the world, with significant implications for how people navigate meaning, morality, and external influences.

Buffered Identity

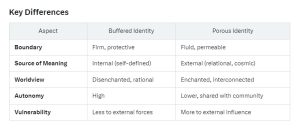

Definition: A “buffered” identity refers to a self that is insulated, autonomous, and distinct from the external world. The individual perceives themselves as having a clear boundary between their inner self (mind, will, or soul) and the outside environment, including nature, society, and supernatural forces.

Characteristics:

Emphasis on self-control, rationality, and independence.

External forces (e.g., spirits, emotions, or social pressures) are seen as separate and manageable, not inherently part of the self.

The self is “buffered” by a sense of detachment or protection from unmediated influence.

Historical Context: This concept is often tied to modernity and the Enlightenment, where disenchantment and secularization fostered a view of the individual as a self-contained agent. Think of Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” — the self is defined by its internal reasoning capacity.

Implications:

Strengths: Promotes personal agency, critical thinking, and resilience against external manipulation. It aligns with individualism and the scientific worldview.

Challenges: Can lead to isolation, a sense of disconnection from community or nature, and an over-reliance on rationality that might dismiss emotional or spiritual dimensions of life.

Porous Identity

Definition: A “porous” identity refers to a self that is open, permeable, and deeply interconnected with the external world. The boundaries between the individual and their surroundings—whether social, natural, or spiritual—are fluid and less defined.

Characteristics:

The self is vulnerable to and shaped by external forces, such as emotions, spirits, traditions, or communal values.

Experiences like enchantment, possession, or collective identity feel natural because the self isn’t rigidly separated from the world.

Meaning and identity are often derived relationally rather than from within.

Historical Context: This is associated with pre-modern or “enchanted” worldviews, where people felt intertwined with a cosmos filled with unseen forces, gods, or communal narratives. For example, medieval peasants might see their fate as tied to divine will or village life.

Implications:

Strengths: Fosters a sense of belonging, humility, and harmony with the environment or community. It can enrich life with a sense of mystery or transcendence.

Challenges: May leave individuals more susceptible to external pressures, superstition, or loss of personal autonomy. It can clash with modern demands for self-determination.

Broader Implications

Cultural Shifts: The move from porous to buffered identities reflects the rise of modernity, but some argue we’re seeing a return to porosity in postmodernity—through spirituality, ecological awareness, or digital interconnectedness (e.g., social media blurring personal boundaries).

Psychological Impact: A buffered self might struggle with existential loneliness, while a porous self might grapple with overwhelm or identity diffusion in a chaotic world.

Social Dynamics: Buffered identities align with individualism and liberal democracies, while porous identities resonate with collectivist societies or tribal structures.

Technology: The internet and AI could be seen as “porosifying” the buffered self—our identities are increasingly shaped by algorithms, online communities, and shared narratives, challenging the notion of an autonomous, insulated self.

In essence, the buffered identity prioritizes a fortified, self-reliant “I,” while the porous identity embraces a relational, open “we.” Neither is inherently superior; the tension between them reflects ongoing human struggles to balance independence with connection in an ever-evolving world.