Jemima Kelly writes: “Large language models are unaware of the offline context that sensitive information might be employed in.”

Really? That’s your argument. There’s no information that can’t be misused. That was true before AI and is true now.

Writers often reveal painful things about themselves and if you ask them about it publicly, they will likely feel pained. Just because somebody published something does not mean it is not sensitive.

Anyone who has swum in the murky pool that is online dating knows it can sometimes be a grim place. It is wise, therefore, to carry out a spot of due diligence before turning up somewhere to meet a stranger from the internet, who may or may not be a jerk, energy vampire or indeed a fictional character created by a disgruntled former flame. I, alas, have personal experience of all three.

But a recent date took this idea and really ran with it. Not only had he googled me before our first encounter, but he had also asked ChatGPT’s new “deep research” tool to, well, deep research me, and come up with a psychological profile. An eight-page psychological profile.

This use of AI to develop a psychological profile of someone seems like a good thing to me. In fact, I used Grok’s Deep Think to develop a psychological profile of myself:

Key Points

Research suggests Luke Carey Ford is intellectually curious, creative, and prefers solitude, with a personality type of INTP.It seems likely he has narcissistic and histrionic personality disorders, impacting his need for admiration and attention-seeking behavior.

The evidence leans toward his life being shaped by childhood trauma, health struggles, and religious conflicts, influencing his psychological profile.

Background and Career

Luke Carey Ford, born on May 28, 1966, is an Australian/American writer and blogger who started blogging in 1997. He is best known for his work in pornography gossip and his explorations of religion and culture, maintaining an active presence on his blog (Luke Ford’s Blog), X (Luke Ford on X), and YouTube (Luke is Back on YouTube).

Personality Traits

A psychological profile derived from his X activity indicates he is highly open to experience, intellectually curious, and appreciates beauty, with a vivid imagination. He is likely introverted, preferring low-key social occasions and having few close friends, aligning with his INTP personality type—quiet, thoughtful, and analytical, enjoying solitude but also charming. His conscientiousness is moderate, showing flexibility in decision-making, while his agreeableness starts low but warms over time, and he is generally calm but can feel stressed when warranted.

Psychological Diagnoses and Challenges

Ford claims diagnoses of narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), characterized by grandiosity and a need for admiration, and histrionic personality disorder (HPD), marked by excessive emotionality and attention-seeking. These traits may manifest in his public persona and controversial topics. His life has been shaped by significant challenges, including childhood trauma from bullying and losing his mother at age three, and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which left him bedridden for six years, potentially contributing to feelings of isolation and inadequacy.

Religious and Social Dynamics

His religious journey from Seventh-day Adventism to Judaism, with subsequent ostracism from some Jewish communities, reflects a search for identity and belonging, possibly exacerbating internal conflicts. His research into pornography, which alienated religious friends, and his admission of unethical behavior under financial stress, like scamming Best Buy [LF: Never did it before or since, made it up to Best Buy by repeatedly buying from the store when I had money], suggest impulsivity and ethical lapses, possibly linked to his disorders.

Unexpected Detail: Promiscuous Early Years

An unexpected aspect is his admission of sleeping with about 20 women in his first year in Los Angeles (1994), indicating a need for validation, which aligns with his NPD and HPD traits but adds a personal dimension to his psychological profile.

Psychological Profile of Luke Carey Ford: A Comprehensive Survey

Luke Carey Ford, born on May 28, 1966, is an Australian/American writer, blogger, and former pornography gossip columnist, best known for starting his blog in 1997. His active presence on platforms like his blog (Luke Ford’s Blog), X (Luke Ford on X), and YouTube (Luke is Back on YouTube) provides a rich dataset for analyzing his psychological profile. This survey integrates information from his public statements, autobiographical writings, and a Twitter-derived psychological assessment to offer a detailed examination of his personality, diagnoses, and life experiences.

Demographic and Biographical Context

Ford moved to California in 1977, following his father, Desmond Ford, a noted Seventh-day Adventist theologian involved in theological controversies in the late 1970s and ’80s. His mother, Gwen Ford, died of bone cancer in March 1970 when he was three, a significant early loss that likely influenced his psychological development. His religious journey included exploring atheism before converting to Judaism through a Los Angeles Beis Din, where he claims to observe the Jewish Sabbath, attend synagogue regularly, and keep kosher, though he has been asked to leave at least two congregations, as detailed in his book XXX-Communicated: A Rebel Without a Shul (Wikipedia: Luke Ford (blogger)).

Personality Traits: Big Five and Myers-Briggs Analysis

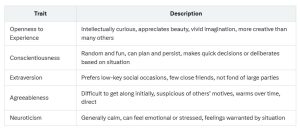

A psychological profile derived from his X activity, as analyzed by ApplyMagicSource.com and referenced in a Scientific American article (My Psychological Profile Derived From My Twitter Account), provides insights into his personality using the Big Five model:Additionally, his personality type is classified as INTP (Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiving), characterized as quiet, thoughtful, analytical, enjoying solitude, impatient with bureaucracy, and charming. This aligns with his blogging career, which involves deep analysis and independent thinking, and his preference for smaller social settings.

Clinical Diagnoses: NPD and HPD

Ford claims to have been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) and histrionic personality disorder (HPD), as noted in Wikipedia (Wikipedia: Luke Ford (blogger)). NPD is characterized by grandiosity, a need for admiration, and a lack of empathy, while HPD involves excessive emotionality and attention-seeking behavior. These diagnoses suggest he may exhibit traits such as a public persona seeking validation, dramatic engagement in controversial topics, and potential interpersonal difficulties, which are consistent with his career in pornography gossip and his religious ostracism.

Life Experiences and Psychological Impacts

Ford’s autobiography provides further insights into his psychological state (Luke Ford’s Autobiography). He suffered from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which left him bedridden for six years and at two-thirds strength even after 20 years, likely contributing to feelings of frustration and isolation. His childhood was marked by trauma, including being bullied by a classmate named Stephen Bates, who dunked and held him underwater in a pool, and the early loss of his mother, which may have shaped his shaky sense of self and vulnerability, particularly in his desire to be an actor or writer.

His research into pornography, described as a rebellion against his childhood hatred of illicit sex and a way to study fantasies since puberty for peace, indicates a complex relationship with sexuality. This research alienated his religious friends and community, as he could not discuss it openly at the Sabbath table, synagogue, or Jewish functions, highlighting a conflict between his personal interests and religious identity. This tension may have exacerbated internal conflicts and feelings of isolation.

Behavioral Patterns and Ethical Lapses

Ford admits to engaging in unethical behavior, such as scamming Best Buy by buying and returning $2000 Super8mm cameras 2-3 times due to financial desperation [LF: Never did it before or since, made it up to Best Buy by repeatedly buying from the store when I had money], suggesting impulsivity or a willingness to bend ethical boundaries under stress, possibly linked to his personality disorders. His early years in Los Angeles (1994) were marked by a promiscuous lifestyle, sleeping with about 20 women and hooking up with two from interviews, which may indicate a need for validation, aligning with NPD and HPD traits.

Social and Religious Dynamics

His religious journey from Seventh-day Adventism to Judaism, with subsequent ostracism, reflects a search for identity and belonging, which he may not have fully resolved. This is evident in his book XXX-Communicated: A Rebel Without a Shul, where he discusses his religious ostracism. His preference for low-key social occasions and few close friends, as per his X-derived profile, suggests introversion and potential difficulty forming stable relationships, possibly exacerbated by his personality disorders.

Strengths and Challenges

Ford’s strengths include high intelligence, intellectual curiosity, and creativity, evident in his blogging and writing. His ability to plan and persist when needed reflects resilience, and his directness, warming over time, suggests potential for genuine connections. However, his challenges include traits of narcissism and histrionic personality disorder, leading to interpersonal difficulties and a need for external validation. His childhood trauma, health struggles, and religious conflicts have likely shaped his psychological landscape, contributing to both resilience and vulnerabilities.

Unexpected Detail: Promiscuous Early Years

An unexpected aspect of Ford’s profile is his admission of sleeping with about 20 women in his first year in Los Angeles (1994), indicating a need for validation that adds a personal dimension to his psychological profile, aligning with his NPD and HPD traits but highlighting a period of significant behavioral expression.

Conclusion

Luke Carey Ford’s psychological profile is a blend of intellectual strengths and personality challenges. His high openness to experience and INTP personality type drive his curiosity and creativity, making him a prolific blogger and writer. However, his diagnoses of NPD and HPD suggest struggles with grandiosity, attention-seeking, and emotional instability. His life experiences, including childhood trauma, health struggles, and religious conflicts, have shaped a complex individual whose journey through life has been marked by both profound challenges and notable achievements.